To view this on the COS website, click here legislator-reference-manual-example-only

To download the pdf file from the COS website, click here Example_Notebook1.pdf

Legislator Reference Manual (Example Only)

Legislator Reference Manual (Example Only)

Attachment: 356/ExampleNotebook1.pdf

|

Photo source: Americans for Prosperity

Continued on page 2

Restore Our Republic

Exploring the Purpose and Power of a Convention of States

The Article V Solution Series

Published March 9–13, 2015

By Rita Martin Dunaway |

| theblaze.com

Washington is broken. Our states have been stripped of their rightful decision-making

authority. Debt is out of control, regulations crush free enterprise, and our freedoms

have been stolen.

But we have a solution as big as the problem.

Article V of the Constitution allows the states to call a Convention of States to

propose constitutional amendments to limit federal spending, debt, and regulations.

A Convention of States is the tool given to us by our Founding Fathers to protect and

restore our Constitution, and thereby protect and restore our Republic.

NOW is the time. Discover exactly what a Convention of States is, how it works, what it

can and cannot do. Then decide:

do you have the courage to join us?

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 1

2

We know that the Founders’ whole purpose for

including the convention mechanism was to provide a

way for the states to bypass Congress in achieving

needed constitutional amendments.

P

erhaps the most unifying conservative

trait is the conviction that our Founding

Fathers designed an ingenious federal sys-

tem that we ought to conserve. But as fed-

eralism lies dying and our society spirals

toward socialism, there is dissension

among conservatives about using the pro-

cedure the Founders left to the states to

conserve it.

Because Article V’s amendment-proposing

convention process has never been used,

some have branded it a mystical and dan-

gerous power — a thing shrouded in mys-

tery, riddled with unanswerable questions,

and therefore best left alone. Some have lit-

erally labeled it a “Pandora’s Box,” the

opening of which would unleash all manner

of evil upon our beleaguered nation.

Article V opponents accuse proponents of

being reckless with the Constitution. They

say we have no idea how a convention

would work, who would choose the dele-

gates, how votes would be apportioned, or

whether the topic of amendments could be

limited.

My task today is to remove the shroud

of mysticism by revealing what we do

know about an Article V convention from

its text, context, historical precedent, and

simple logic.

For starters, we know that the Founders’

whole purpose for including the convention

mechanism was to provide a way for the

states to bypass Congress in achieving

needed constitutional amendments.

An early draft of Article V vested Congress

with the sole power to propose constitu-

tional amendments. Under that version,

two-thirds of the states could petition

Congress to propose amendments, but it

was still Congress that did the proposing.

On Sept. 15, 1787, George Mason strenu-

ously objected to this, pointing out that such

a system provided no recourse for the states

if the national government should become

tyrannical, as he predicted it would do.

The result was the unanimous adoption of

Article V in its current form, providing two

ways for constitutional amendments to be

proposed: Congress can propose them, or

the states can propose amendments at a con-

vention called by Congress upon application

from two-thirds, or 34, of the states.

Regardless of which body proposes the

amendments, proposals must be ratified by

three-fourths, or 38, of the states in order to

become effective.

We also know from history that voting at an

Article V convention would be done on a

one-state, one-vote basis. This is the univer-

sal precedent set by the 32 interstate con-

ventions that occurred prior to the

Constitution’s drafting. It explains why it

was unnecessary for Article V to specify the

number of delegates to be sent by each state;

the states can send as many delegates as

they like, but each state only gets one vote.

We know that state legislatures choose and

instruct their convention delegates who act

as agents of the state legislatures. Again, this

is a matter of universal historical precedent

for interstate conventions.

On Nov. 14, 1788, the Virginia General As-

sembly filed the very first application for an

Article V Convention to propose a bill of

rights and aptly branded the convention a

“convention of the States” to be composed

of “deputies from the several States.”

Because Congress ultimately used its own

Article V power to propose a bill of rights,

that meeting was rendered unnecessary. But

the application demonstrates the contempo-

raneous understanding that the convention

process was state-led. The Supreme Court

has likewise referred to the process as a

“convention of states.”

The Article V Solution — Demystifying a Dusty Tool

by Rita Martin Dunaway

|

March 9, 2015

1

Continued to page 3

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 2

3

F

ar and away, fear is the most common

rationale among opponents of Article

V’s convention process for proposing con-

stitutional amendments. Fear of the uncer-

tain result, fear of a Congressional

take-over, fear of George Soros and what

his money might buy.

But even as naysayers sit in their meeting

rooms and chat rooms opining about hy-

pothetical rogue delegates to a hypotheti-

cal convention, Congress continues to

spend money that our great-grandchildren

will one day owe.

Our president continues to use creative

legal arguments to erase the lines that once

separated constitutional powers, thrusting

himself into the business of lawmaking.

Unelected bureaucrats continue to churn

out mountains of regulations that are unau-

thorized by Congress—and in some cases

put hardworking Americans out of work.

And the Supreme Court is one vote away

from a revocation-through-interpretation

of our right to bear arms.

Rather than checking and balancing one

another as they were designed and em-

powered to do, the three branches of the

federal government are acting in concert

to further concentrate their power at the

expense of state prerogatives and individ-

ual liberty.

All three branches are, effectively, making

laws. Congress, the intended lawmaking

branch, has extended its lawmaking into

matters reserved to the states. And our un-

accountable Supreme Court finds inven-

tive ways to interpret the Constitution so

as to justify this—not because it can’t de-

termine the Constitution’s original mean-

ing, but because the original meaning

doesn’t matter if our Constitution is, as we

are told, a “living, breathing document.”

Meanwhile, administrative agencies—the

bold and unmanageable fourth branch of

government—have broken the will of the

American people by the sheer volume of

their regulations, rules, and reports. The

Environmental Protection Agency’s 376-

page “Regulatory Impact Analysis” for its

War on Coal begins with a five-page list

of acronyms to be learned by the aspiring

reader—a virtual electric fence to all but

the most intrepid citizen.

How can we be a self-governing people

when we are completely removed from the

invisible hands that actually regulate us,

with no means of holding them account-

The Article V Solution — The Absurdity of Inaction

by Rita Martin Dunaway

|

March 10, 2015

Ph

ot

o

so

ur

ce

: A

P

Ph

ot

o/

C

ha

rle

s

D

ha

ra

pa

k

Continued on page 4

All three branches are, effectively, making laws.

2

Finally, we know that the topic(s) specified

in the convention applications does matter.

Over 400 applications for an Article V con-

vention have been filed since the drafting of

the Constitution. The reason we have never

had one is because there have never been 34

applications seeking a convention for the

same purpose(s). The state applications con-

tain the agenda for an Article V convention,

and until 34 states agree upon a convention

agenda, there will be no convention.

Because the authority for an Article V con-

vention is derived from the 34 state appli-

cations that trigger it, the topic(s) for

amendments specified in those applications

is a binding limitation on the scope of the

convention.

The “unanswerable” questions about Arti-

cle V do have answers. The unshrouded Ar-

ticle V convention isn’t a Pandora’s Box at

all, because there is no such thing as magic

in a box for us to fear—there is only history,

law, and reason to guide faithful Americans

in tending their government. And precisely

because there is no such thing as magic,

we’re going to need an effective tool to do

the hard work of restoring our Republic.

It’s time to dust off the tool the Founders

gave us in Article V and get started.

n

Continued from page 2

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 3

4

able, and no hope of knowing or under-

standing the laws they are making?

Many who oppose using Article V’s con-

vention process would agree that well-de-

signed constitutional amendments could

close court-created structural loopholes

that have damaged our federal structure

and concentrated power in Washington,

D.C. For instance, we could require con-

gressional approval for all administrative

regulations. We could clarify where Con-

gress’ authority ends and the states’ author-

ity begins so that Congress could actually

have time to do its constitutional job.

Yet some insist that an amendment-

proposing convention amounts to open-

heart surgery for our Constitution, and that

nothing could ever justify such an action.

Newsflash: our beloved Constitution has

been on the operating table, under the knife

of an activist Supreme Court, for decades.

An admittedly imperfect but well-prepared

team of doctors is standing by, eager to

stop the bleeding and close up the wound.

But a fearful crowd of skeptics is blocking

the way. They love this patient and are not

entirely convinced that the doctors’ train-

ing is sufficient. Do they have the proper

supplies? What if armed gunmen enter the

surgical ward and interrupt the lifesaving

process?

“No,” the skeptics conclude. “We can’t be

assured of a good outcome, so we had bet-

ter just stand by.”

And the patient’s life ebbs away.

We could learn a lot from Dietrich Bonho-

effer, the German pastor who resolved to

actively resist Adolf Hitler, at any cost.

Bonhoeffer had a painful understanding

that it is our actions—not our sentiments—

that reveal our truest convictions, and that

our desire for safety can be an obstacle to

the action that our professed morality re-

quires. In 1934, he explained:

“There is no way to peace along the

way of safety. For peace must be

dared. It is itself the great venture and

can never be safe. Peace is the oppo-

site of security.”

It was also Bonhoeffer who said, “Not to

act is to act.”

The Founding Fathers gave us a tool in

Article V to restrain federal power

through state-proposed constitutional

amendments. I do not doubt that the

conservatives trying to block the use of

this tool have sincere reverence for our

founding document. But mere sentiments

cannot rescue our Constitution from con-

tinued disfiguration under the federal

scalpel, nor close the wounds that are

standing open even as we continue this

debate.

n

Continued from page 3

The Supreme Court is one vote away from a revocation-through-

interpretation of our right to bear arms.

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 4

5

The Article V Solution —

The Way to Implement the 10

th

Amendment

by Rita Martin Dunaway

|

March 11, 2015

The powers not

delegated to the United

States by the Constitution,

nor prohibited by it to the

states, are reserved to

the states respectively,

or to the people.

I

t’s the elephant in the room. The 10

th

Amendment boldly declares:

“The powers not delegated to the

United States by the Constitution, nor

prohibited by it to the states, are re-

served to the states respectively, or to

the people.”

But if the daily news is any indication,

there is no subject exempt from federal

power. Through its power of the purse,

which is virtually unlimited under the mod-

ern interpretation, Congress can impact, in-

fluence, or coerce behavior in nearly every

aspect of life.

The question, then, that holds the key to

unlocking our constitutional quandary is

this: how do states protect their reserved

powers under the 10

th

Amendment?

On a piecemeal basis, states can certainly

challenge federal actions through lawsuits,

arguing that the federal government lacks

constitutional authority to act in a particu-

lar area. But what if the court, as it is wont

to do, “interprets” the Constitution as pro-

viding the disputed authority? What then?

In their frustration and disbelief over the

growing extent of federal abuses of power

(and the refusal of our Supreme Court to cor-

rect them), some conservatives argue that

states should engage in “nullification,”

whereby the states simply refuse to comply

with federal laws they deem unconstitutional.

While there are some, less dramatic forms

of nullification that are perfectly appropri-

ate and constitutional—such as states re-

fusing to accept federal funds that come

attached to federal requirements—this

state-by-state, ad hoc review of federal law

is fraught with legal and practical pitfalls.

First of all, which state officer, institution,

or individual decides whether a federal ac-

tion is authorized under the Constitution?

Is it the state supreme court, the legislature,

the attorney general—or can any individual

make the determination? After all, the 10

th

Amendment reserves powers to individuals

as well as to states.

Secondly, how can a state enforce its nul-

lification of a federal law? For instance, if

a state decides that the Affordable Care

Act’s individual mandate is unconstitu-

tional, how can it protect its citizens

against the “tax” that will be levied against

them if they fail to comply? It’s difficult to

envision an effective nullification enforce-

ment method that doesn’t end, at some

point, with armed conflict.

But for true conservatives whose goal is to

conserve the original design of our federal

system, the far more fundamental problem

with this type of in-your-face nullification

is the fact that it was not the Founders’ plan.

Article VI tells us that the Constitution and

federal laws passed pursuant to it are the

“supreme law of the land.” Under Article

III, the United States Supreme Court is

considered to be the final interpreter of the

Constitution. While some claim that this

was not the Founders’ intention, historical

records such as Alexander Hamilton’s Fed-

eralist 78 demonstrate it was, in fact, the

judiciary that they intended to assess the

constitutionality of legislative acts.

And then we have the 10

th

Amendment it-

self. It establishes a principle, but it does

not establish a remedy or process for pro-

tecting the reserved powers from federal

intrusion.

That missing process is found in Article V.

Faced with a federal government acting be-

yond the scope of its legitimate powers—

and a Supreme Court that adopts erroneous

interpretations of the Constitution to justify

the federal overreach—the states’ constitu-

tional remedy is to amend the Constitution

to clarify the meaning of the clauses that

have been perverted. In this way, the states

can assert their authority to close the loop-

holes the Supreme Court has opened.

You don’t have to take my word for it.

In an 1830 letter to Edward Everett, James

Madison said:

“Should the provisions of the Constitu-

tion as here reviewed be found not to se-

cure the Government and rights of the

States against usurpations and abuses on

the part of the United States, the final re-

sort within the purview of the Constitu-

tion lies in an amendment of the

Constitution according to a process ap-

plicable by the States.”

In other words, Article V is the ultimate nul-

lification procedure. For states that have the

will to stand up and assert their 10

th

Amend-

ment rights, they can do so by applying for

an Article V convention to propose amend-

ments that restrain federal power.

n

3

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 5

The Article V Solution —

The Founders Would Want Us To Use It

by Rita Martin Dunaway

|

March 12, 2015

4

6

A

s I have explained in previous articles

in this series, most conservative oppo-

nents to Article V’s convention process are

people who revere our Founding Fathers

and the Constitution they created.

While the brave and brilliant men who de-

vised our ingenious federal system are

certainly deserving of our profound re-

spect, admiration, and gratitude, the idea

that they were perfect, infallible states-

men—and that the Constitution is un-

touchable Holy Writ—is antithetical to

their own worldview. And it is this world-

view that inspired our government’s

unique design.

Federalist 51 says it best:

“It may be a reflection on human na-

ture, that such devices should be nec-

essary to control the abuses of

government. But what is government

itself, but the greatest of all reflections

on human nature? If men were angels,

no government would be necessary. If

angels were to govern men, neither ex-

ternal nor internal controls on govern-

ment would be necessary. In framing a

government which is to be adminis-

tered by men over men, the great diffi-

culty lies in this: you must first enable

the government to control the gov-

erned; and in the next place oblige it to

control itself.”

Thus, the Constitution establishes a gov-

ernment replete with checks and balances

designed to make “ambition to counteract

ambition.”

At least, that was the plan. As I explained

in a previous article, the three branches of

our federal government are now acting in

concert to further concentrate federal

power at the expense of state power and

individual liberty.

The Founders predicted this and planned

for it. They provided the states with a

means of imposing additional checks on

all three branches of the federal govern-

ment. They designed Article V’s conven-

tion process specifically to correct any

improper aggregation of power.

Good government is simply not a once-

and-for-all proposition. At a minimum, it

requires our continual exertion to elect

“good” public officials. But because we

don’t do that perfectly, and because even

“good” public officials aren’t perfect, good

government requires various adjustments,

at various times, to realign its operating

structure with the blueprint.

The bold declaration that “all men are

created equal, that they are endowed by

their Creator with certain unalienable

rights” was entirely inconsistent with the

ongoing practice of slavery at our found-

ing. It was perfect in principle, yet de-

manded the blood, sweat and tears of

“In framing a

government which

is to be administered

by men over men,

the great difficulty

lies in this: you must

first enable the

government to control

the governed; and in

the next place oblige

it to control itself.”

Continued on page 7

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 6

7

future generations — and a constitutional

amendment — to effectuate.

Most modern inconsistencies between

constitutional principle and practice result

from interpretations of the language that

conflict with its original meaning. Because

the natural ambition of man has led con-

gresses, presidents, and courts to seize

power at every point of textual vagueness

or ambiguity, modern Americans now con-

front the task of solidifying the original

structure and fortifying limitations on fed-

eral power.

We must use the tools at our disposal to

conform our government’s operating

structure to the blueprint.

I once assembled a desk using pre-fabri-

cated components, a few tools, and an in-

struction booklet. When the project was

finished, I discovered that I had inadver-

tently fastened the drawer to the desktop

in such a way that the drawer cannot be

opened.

Now I can shout, “Open!” at the drawer,

or I can complain about my faulty inter-

pretation of the instructions, but the only

way I will ever achieve a functioning

drawer is to remove the improperly con-

structed pieces and replace them, paying

careful attention to the instructions.

Our Constitution is the operating manual

for our government. At times, those

charged with interpreting the manual have

erred, and erred badly. The result is a dys-

functional federal system.

Those who have read the instructions and

understood them can shout “Obey the

Constitution!” to federal officials. We can

be angry at those who have either purpose-

fully or incompetently interpreted the

manual to produce the mutated system we

have today. But none of this will set things

right.

The only way we will ever return to a

properly functioning federal system is by

repairing the damage that has been done to

it through specific, unambiguous constitu-

tional amendments that reject and replace

the offending workmanship.

It isn’t disloyal to the Founders to propose

constitutional amendments. In fact, the

surest way to honor their legacy is to em-

ulate them. They knew themselves to be

imperfect, and yet they summoned their

courage and acted in pursuit of the high

ideal of self-governance. We must do like-

wise.

n

Continued from page 6

Continued on page 8

The Article V Solution —

Courage Is the Price of Liberty

by Rita Martin Dunaway

|

March 13, 2015

T

hroughout this series, I have argued

t h a t a n A r t i c l e V a m e n d m e n t -

proposing convention offers a viable and

well-designed process for the states to rein

in a runaway federal government and

restore our Republic. In fact, I believe this

process may well be the only way to

close the court-created loopholes to our

Constitution’s original limitations on

federal power.

The process is as safe as any political

process can be, entailing numerous, redun-

dant protections.

First, the scope of authority for the con-

vention is set by the topic(s) specified in

the 34 applications that trigger the conven-

tion. So if 34 states apply for a convention

to propose amendments that limit federal

power, any proposals beyond that scope

would be out of order.

Second, state legislatures can recall any

delegates who exceed their authority or

instructions. As a matter of basic agency

law, actions taken outside the scope of a

delegate’s authority would be void.

Third, even if a majority of convention

delegates went rogue and were left

unchecked by the state legislatures they

represent, and even if Congress neverthe-

Courage was the ink

that marked the words

of the Declaration of

Independence onto the

opening chapter of

America. It was the boat

that carried Gen. George

Washington across the

Delaware River.

5

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 7

8

Continued from page 7

less sent the illicit amendment proposals

to the states for ratification, the courts

could intervene to declare the proposals

void. While the courts don’t have a won-

derful track record in interpreting broad

constitutional language, they do have an

excellent track record of enforcing clear,

technical matters of procedure and

agency law.

But the most important protection on the

Article V process is the explicit constitu-

tional requirement that three-fourths,

or 38, of the states must ratify any pro-

posed amendments in order for them to

become effective. This means that any

bad amendment can be blocked by only

13 states.

In light of the multiple layers of protection

on the state-led Article V convention

process, it is difficult to understand why

some are so afraid of it–or why they don’t

seem to fear Congress’ parallel Article V

power to propose amendments on any sub-

ject, any day it sits in session.

Certainly, no future outcome of any kind

can ever be absolutely guaranteed. Day

has dawned since the beginning of time,

but who can definitively prove that the sun

will rise tomorrow?

What critics must acknowledge, however,

is that the proper risk analysis is a compar-

ative one. It would be difficult for anyone

to maintain, with a straight face, that the

risk of a state-led amendment-proposing

convention is greater than the risk of stay-

ing our current course.

The “risk” (which, again, exists only in the

sense that nothing is entirely risk-free) is

negligible. But to those who can’t see

around it, I posit this: Courage is the price

of liberty. It always has been, and it always

will be.

Courage was the ink that marked the

words of the Declaration of Independence

onto the opening chapter of America. It

was the boat that carried Gen. George

Washington across the Delaware River.

Courage was the tattered uniform of young

men who gave their lives to rid a fledgling

America of the scourge of slavery. It

was the tank that carried weary soldiers

over the battlefields of a Hitler-stained

Europe. And courage was the voice of

Martin Luther King, Jr., challenging

America to end her hypocrisy and make

good on her commitment to the legal

equality of mankind.

America exists because our forefathers

pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their

sacred honor to secure for us the blessings

of liberty and the right of self-governance.

They left us Article V’s convention

process to ensure that we would have a

final defense against federal tyranny. If our

generation is so frozen in fear that we lack

the modicum of courage required to hold

a meeting, then we are simply unworthy of

our heritage.

Courage is the price of liberty.

To learn how you can get involved in this

historic effort to restore our Republic, visit

www.conventionofstates.com.

n

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as

Staff Counsel for The Convention

of States Project and is

passionate about restoring

constitutional governance in the

U.S. Follow her on Facebook

(Rita Martin Dunaway) and e-mail

her at [email protected]

Connect with

Convention of States

Website: ConventionofStates.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: (540) 441-7227

Facebook:

www.Facebook.com/ConventionOfStates

Twitter: @COSProject

The Convention of States

is a project of

Connect with

Citizens for

Self-Governance

Website: SelfGovern.com

Email: [email protected]

Phone: (512) 943-2014

Facebook:

www.Facebook.com/Citizens4sg

Twitter: @SelfGovernance

COS-Blaze Dunaway July15Layout 1 7/14/15 1:02 PM Page 8

We can’t walk

boldly into our

future, without

first understanding

our history.

Some people contend that our Constitution

was illegally adopted as the result of a “run-

away convention.” They make two claims:

1.

The convention delegates were instructed

to merely amend the Ar ticles of

Confederation, but they wrote a whole

new document.

2.

The ratification process was improperly

changed from

13

state legislatures to

9

state ratification conventions.

The Delegates Obeyed Their

Instructions from the States

The claim that the delegates disobeyed

their instructions is based on the idea that

Congress called the Constitutional

Convention. Proponents of this view

assert that Congress limited the delegates

to amending the Articles of Confederation.

A review of legislative history clearly reveals

the error of this claim. The Annapolis

Convention, not Congress, provided the po-

litical impetus for calling the Constitutional

Convention. The delegates from the

5

states

participating at Annapolis concluded that a

broader convention was needed to address

the nation’s concerns. They named the time

and date (Philadelphia; second Monday

in May).

The Annapolis delegates said they were going

to work to “procure the concurrence of the

other

States

in the appointment of

Commissioners.” The goal of the upcoming

convention was “to render the constitution of

the Federal Government adequate for the ex-

igencies of the Union.”

What role was Congress to play in calling the

Convention? None. The Annapolis delegates

sent copies of their resolution to Congress

solely “from motives of respect.”

What authority did the Ar ticles of

Confederation give to Congress to call such

a Convention? None. The power of Congress

under the Articles was strictly limited, and

there was no theory of implied powers. The

states possessed residual sovereignty which

included the power to call this convention.

Seven state legislatures agreed to

send delegates to the Constitutional

Convention

prior to the time that

Congress acted to endorse it

.

The states

told their delegates that the purpose of the

Convention was the one stated in the

Annapolis Convention resolution: “to render

the constitution of the Federal Government

adequate for the exigencies of the Union.”

Congress voted to endorse this Convention

on February

21, 1787

. It did not purport to

“call” the Convention or give instructions to

the delegates. It merely proclaimed that “in

the opinion of Congress, it is expedient” for

the Convention to be held in Philadelphia on

the date informally set by the Annapolis

Convention and formally approved by

7

state legislatures.

Ultimately,

12

states appointed delegates. Ten

of these states followed the phrasing of the

Annapolis Convention with only minor vari-

ations in wording (“render the Federal

Constitution adequate”). Two states, New

York and Massachusetts, followed the for-

mula stated by Congress (“solely amend the

Articles” as well as “render the Federal

Constitution adequate”).

Every student of history should know that

Can We Trust the Constitution?

Answering The “Runaway Convention” Myth

Michael P. Farris, JD, LLM, Convention of States Action — Senior Fellow for Constitutional Studies

Continued to back page

Continued from front page

History tells the story.

The Constitution was legally adopted.

Now, let’s move on to getting our

nation back to the greatness the

Founders originally envisioned.

the instructions for delegates came from

the states. In

Federalist 40

, James Madison

answered the question of “who gave the

binding instructions to the delegates.” He

said: “The powers of the convention ought,

in strictness, to be determined by an inspec-

tion of the commissions given to the mem-

bers by their respective constituents [i.e. the

states].” He then spends the balance of

Federalist 40

proving that the delegates

from all 12 states properly followed the di-

rections they were given by each of their

states. According to Madison, the February

21

st

resolution from Congress was merely

“a recommendatory act.”

The States, not Congress, called the

Constitutional Convention. They told

their delegates to render the Federal

Constitution adequate for the exigencies of

the Union. And that is exactly what

they did.

The Ratification Process Was

Properly Changed

The Articles of Confederation required any

amendments to be approved by Congress

and ratified by all

13

state legislatures.

Moreover, the Annapolis Convention and

a clear majority of the states insisted that

any amendments coming from the

Constitutional Convention would have to

be approved in this same manner—by

Congress and all

13

state legislatures.

The reason for this rule can be found in the

principles of international law. At the time,

the states were sovereigns. The Articles of

Confederation were, in essence, a treaty be-

tween

13

sovereign nations. Normally, the

only way changes in a treaty can be ratified

is by the approval of all parties to the treaty.

However, a treaty can provide for some-

thing less than unanimous approval if all the

parties agree to a new approval process be-

fore it goes into effect. This is exactly what

the Founders did.

When the Convention sent its draft of the

Constitution to Congress, it also recom-

mended a new ratification process.

Congress approved both the Constitution

itself and the new process.

Along with changing the number of re-

quired states from

13

to

9

, the new ratifica-

tion process required that state

conventions ratify the Constitution rather

than state legislatures. This was done in ac-

cord with the preamble of the

Constitution—the Supreme Law of the

Land would be ratified in the name of “We

the People” rather than “We the States.”

But before this change in ratification

could be valid,

all 13 state legislatures

would also have to consent to the new

method.

All 13 state legislatures did

just this by calling conventions of the

people to vote on the merits of

the Constitution.

Twelve states held popular elections to vote

for delegates. Rhode Island made every

voter a delegate and held a series of town

meetings to vote on the Constitution. Thus,

every state legislature consented to the new

ratification process thereby validating the

Constitution’s requirements for ratification.

Those who claim to be constitutionalists

while contending that the Constitution

was illegally adopted are undermining

themselves. It is like saying George

Washington was a great American hero,

but he was also a British spy. I stand with

the integrity of our Founders who

properly drafted and properly ratified

the Constitution.

Website: ConventionOfStates.com

E-mail: [email protected]

Phone: (540) 441-7227

www.Facebook.com/ConventionOfStates

Twitter: @COSProject

The First-Ever Article V

Convention of States Simulation

~ A Historic Endeavor ~

of

Executive Summary

50 State Delegations Unite to

Pursue Federal Restraints

C

ONVENTION

O

F

S

TATES

.

COM

Mark Meckler

President & Co-Founder

106 E 6

th

Street

Suite 900

Austin, TX 78701

Office: 530-274-9900

[email protected]

1

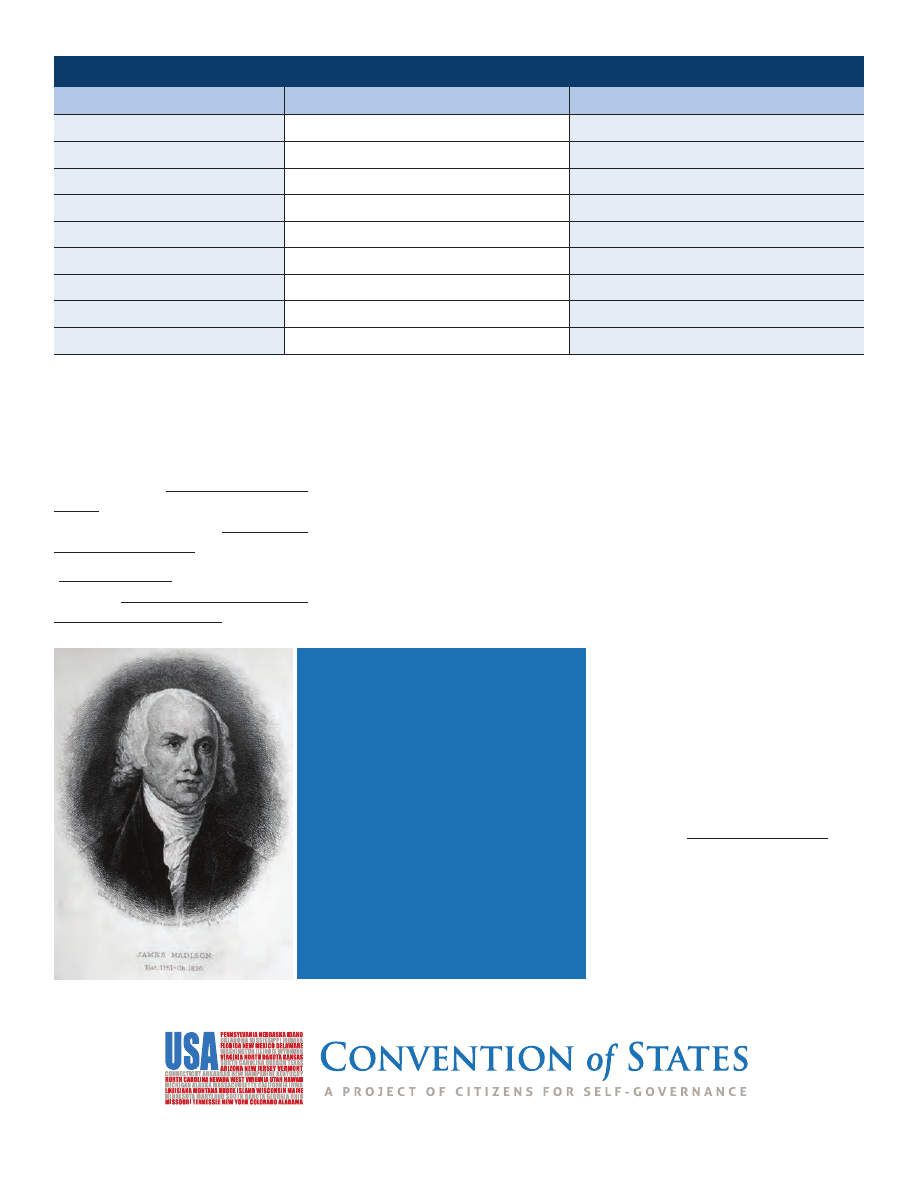

Table of Contents

Page

INTRODUCTION

The First Ever Convention of States Simulation

3

OPENING SUMMARY

Convention Opening Plenary Session

5

COMMITTEE SUMMARIES

Fiscal Restraints Committee

7

Federal Legislative & Executive Jurisdiction Committee

8

Term Limits & Federal Judicial Jurisdiction Committee

10

CLOSING SUMMARY

Convention Closing Plenary Session

11

LASTING IMPRESSIONS OF CONVENTION SIMULATION

Concluding Letter to Commissioners from Simulation President, Rep. Ken Ivory (UT)

17

Commissioners & Legal Advisors Lasting Impressions

18

COMMITTEE ON FISCAL RESTRAINTS

Fiscal Restraints Committee Official Report

21

Citizen Proposed Amendments: Fiscal Restraints

22

COMMITTEE ON FEDERAL LEGISLATIVE & EXECUTIVE JURISDICTION

Federal Legislative & Executive Jurisdiction Committee Official Report

25

Citizen Proposed Amendments: Federal Legislative & Executive Jurisdiction

27

COMMITTEE ON TERM LIMITS & FEDERAL JUDICIAL JURISDICTION

Term Limits & Federal Judicial Jurisdiction Committee Official Report

31

Citizen Proposed Amendments: Term Limits & Federal Judicial Jurisdiction

32

FINAL CONVENTION REPORT & STATEMENT TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE

Official Proposed Amendments, Passed out of the Convention of States Simulation

35

APPENDIX

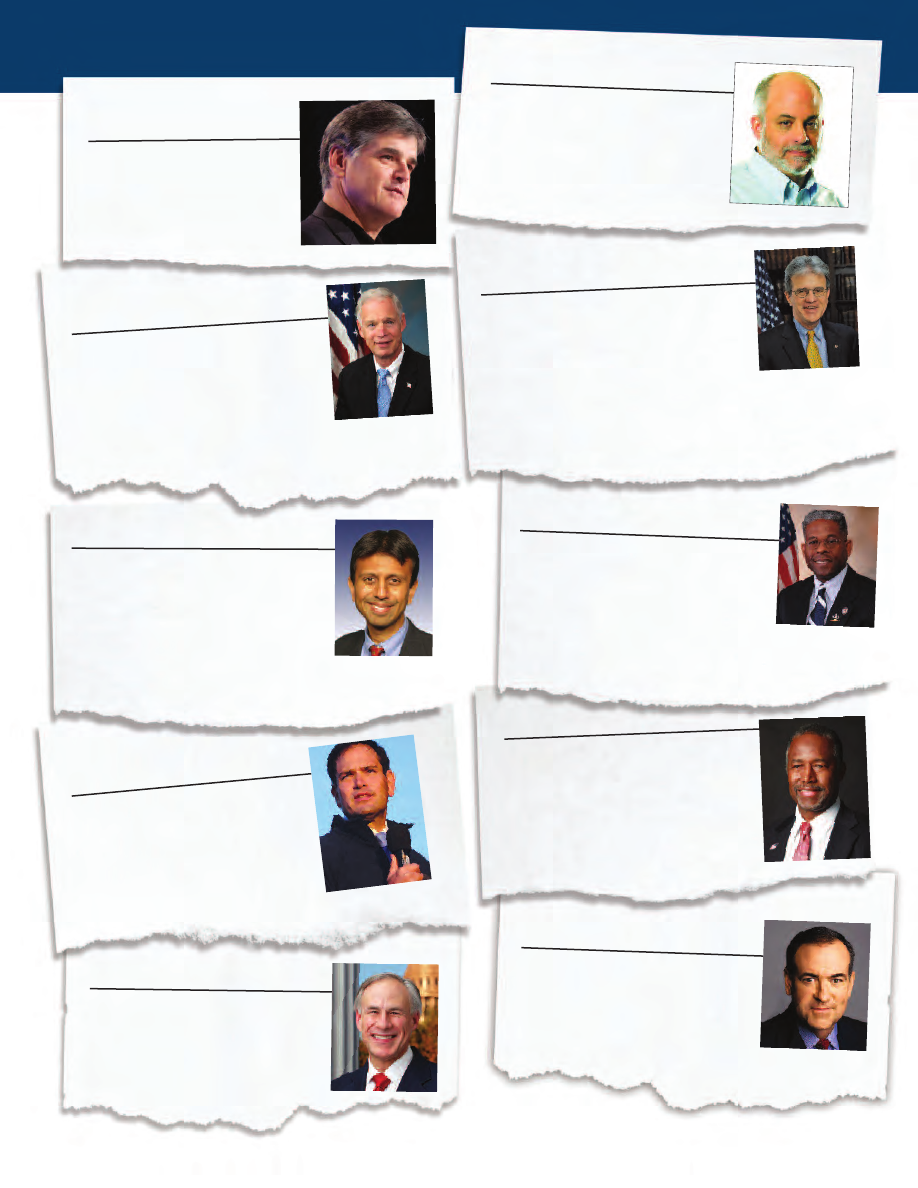

Leadership of the Convention of States Project

37

Roster of State Delegations

39

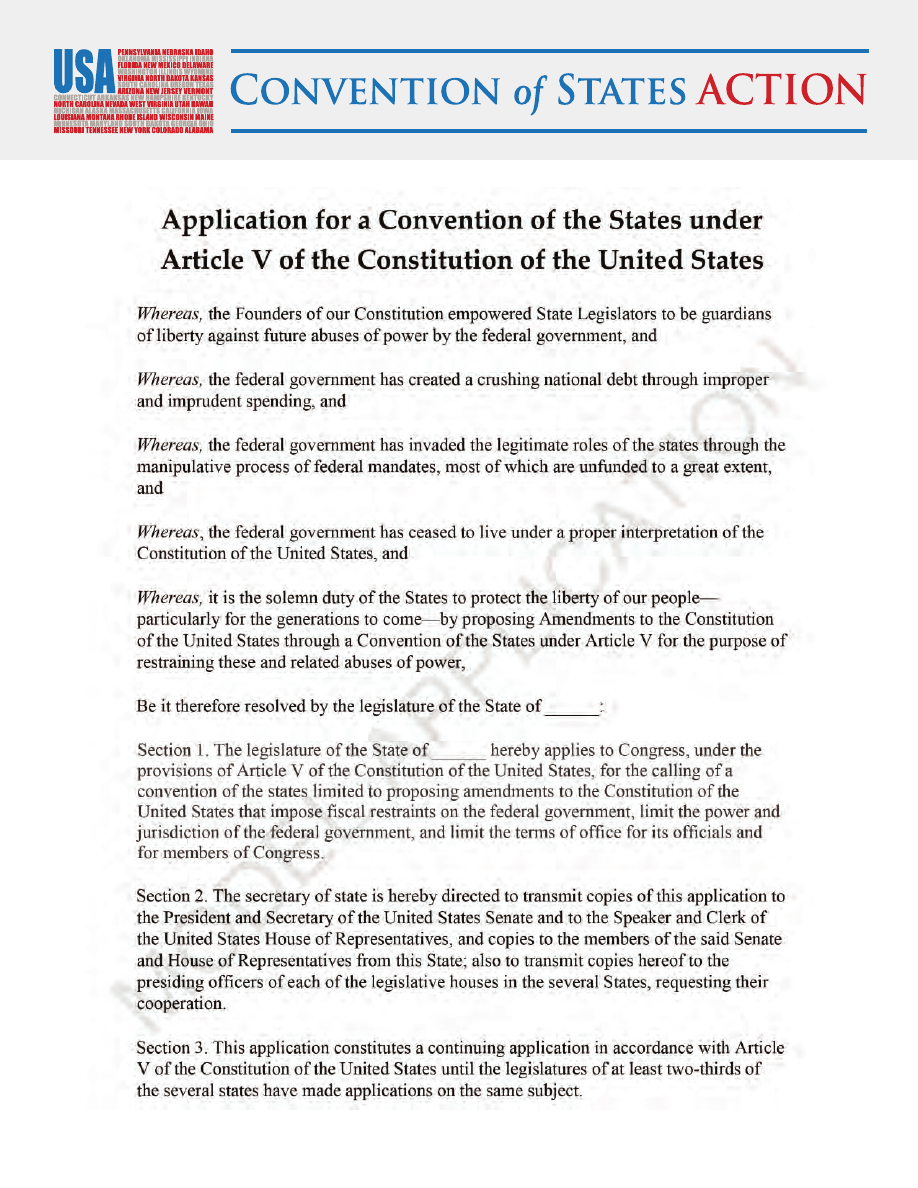

Convention of States Application

42

Proposed Convention Rules

43

TA

BLE

OF

C

ON

TE

N

TS

2

3

INTRODUCTION

The First Ever Convention of States Simulation - A Historic Endeavor

On September 22nd, a historic event began in Colonial Williamsburg.

Every

state in the Union was present for

the first-ever Simulated Article V Convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution.

A total of 137 Commissioners, including 115 sitting state legislators and 22 non-legislator citizens took part in

testing this long-neglected constitutional process with the set of draft rules developed by constitutional experts

Professor Robert Natelson and Michael Farris, and reviewed by the COS Caucus, to guide the process.

These 137 Commissioners came to the Simulation representing a broad and diverse range of state and regional

concerns. They came from greatly varying political experiences. Their constituencies ranged from poor inner-

city Americans to the wealthy, affluent movers and shakers of society. But they all came with this common

political bond: the recognition that Washington, D.C. has overstepped its bounds and operated unchecked for

far too long.

The goal of the Simulation was threefold:

1.

Educate Legislators. The Article V Convention of

States process has never been used. It was important to bring

legislators together from all over the country, to use the

process, run a convention according to the rules, and thereby

create “experts” who would then have a deep, personal

knowledge of how the process actually works.

2.

Build a Network of State Legislators. We know the

power of having a network of educated grassroots in all fifty

states, and based on that model, we believed that it was

imperative to build a similar network of state legislators

committed to the Article V cause. The synergistic effect of

The Simulation proved that the

Article V Convention process is

safe and effective.

IN

TR

O

D

U

C

TI

ON

4

working in a group with a common goal was part of the end game of the Simulation.

3.

Prove that a Convention Works. An Article V convention has never been held before, so it was

important to show proof of concept. We can talk about an Article V Convention of States all we want,

but until we demonstrated one, it was all theory.

The Simulation unfolded seamlessly. The Commissioners built relationships that are continuing. The rules

worked flawlessly. The limited call was obeyed and there was not even a hint of a “run away.” But most

important of all, the Simulation engaged ordinary Americans in a meaningful exercise of self-governance and

proved that state legislators are responsive to the people.

Several weeks prior to the Simulation, Convention of States Senior Fellow for Constitutional Studies, Michael

Farris, hosted a live Facebook event for the purpose of training citizens in the art of crafting constitutional

amendment proposals. COS provided a platform for those citizens to submit their own amendment proposals

for consideration by Commissioners at the Simulation.

Of course, COS’s team of lawyers and experts had its own slate of favored proposals. But the mission of Citizens

for Self-Governance is not to push our own ideas for reforming our nation—it’s to educate and engage the

people

to advocate for the reforms

they

believe are needed to restore our constitutional republic.

So yes, the Simulation proved that the Article V Convention process is safe and effective. But even more

importantly, the thousands of citizen-drafted proposals that formed the basis of the Simulation’s deliberations

proved that Americans are ready to be an engaged, self-governing people again and that State Legislators are

ready to listen.

This handbook will give you an inside view of the Simulation’s proceedings from the perspective of the people

who were there. Enclosed you will find:

An account from the Convention Secretary, Robert Kelly, as to what transpired at each of the

Convention’s Plenary Sessions;

An account from each of the Committee Secretaries as to how each Committee meeting

unfolded;

A letter sent by Convention President Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) to the Convention upon its

conclusion;

Closing comments from Commissioners and Legal Advisors;

The Final Report of each Committee meeting, which was delivered to the Convention;

A sampling of proposals from the grassroots, which were submitted to the Commissioners in

advance of the Simulation for their consideration; and

The Final Report of the Convention, including its statement to the American people and the

amendment proposals that were adopted

IN

TR

O

D

U

C

TI

ON

5

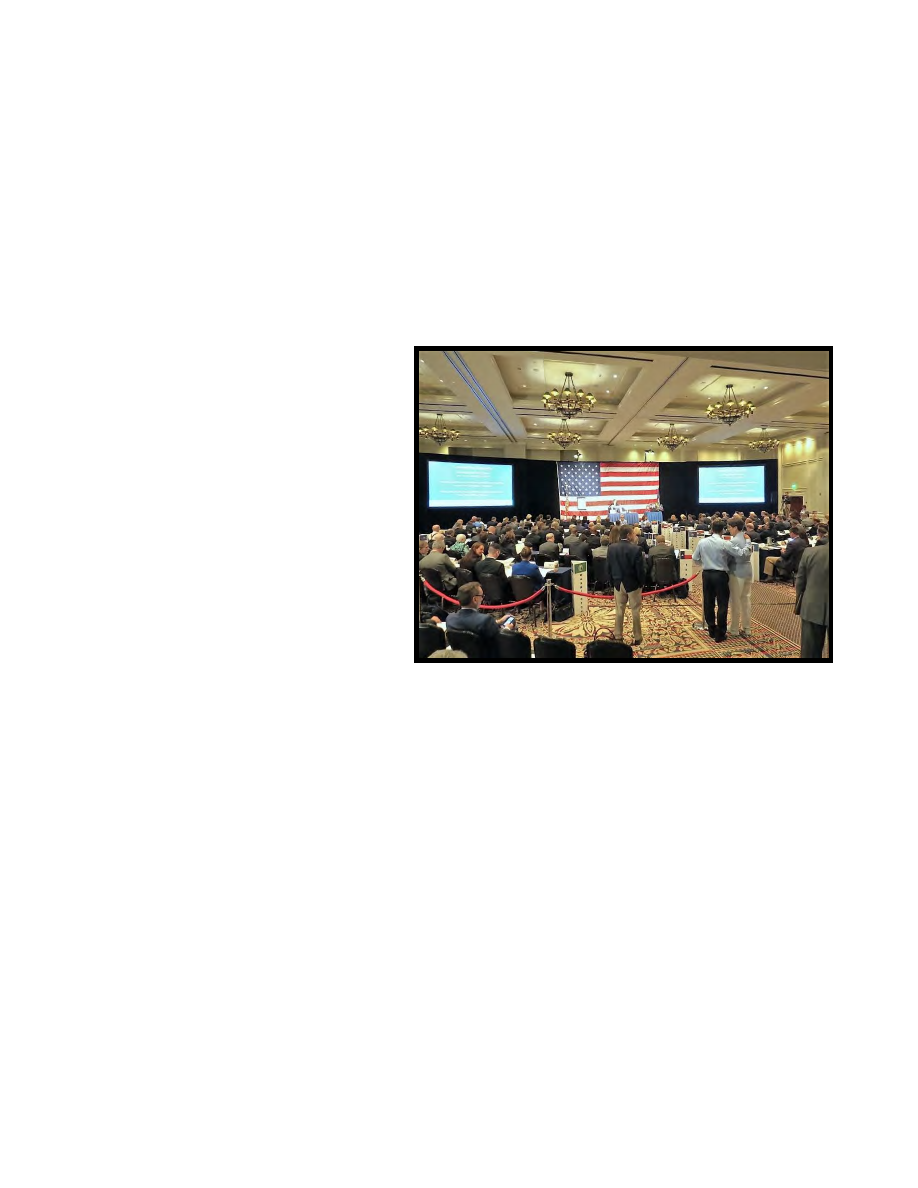

CONVENTION OPENING PLENARY SESSION

At precisely 9:00 on the morning of Thursday, September 22, 2016, the temporary Convention

President, Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA), gaveled the Simulated Convention of States to order. There

was the brief scramble of everyone taking their seats, followed by a moment of silence as everyone

took a deep breath and absorbed the moment.

Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA) ordered the Secretary to

call the roll, and commenced with the business of the

Convention. As the roll was called and each state

indicated its presence the air was thick with a sense of

history in the making. Forty-nine of the fifty states

reported present, with Arkansas shortly to show up.

Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA) noted the existence of a

quorum and invited retired US Sen. Tom Coburn to

offer an invocation for the body. US Sen. Coburn led

the Convention in a solemn prayer to God that He

might assist the Convention in its business and use the

Commissioners as His instruments to turn the direction

of the country back to Him and to its founding

principles.

With a huge American Flag behind the main stage, Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA) led the Convention in

the Pledge of Allegiance. It is hard to imagine a more patriotic and solemn moment than the convening

of Commissioners from all fifty states, standing together to pledge their fidelity to our great nation,

before beginning the difficult work of debating how to reform and preserve it for our posterity.

As the Commissioners were seated, Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA) addressed the body. He challenged

the Commissioners to rise to the occasion and to take their task seriously. He encouraged them to

serve as an example to the American people so that the people might realize they need not look to

Washington to solve the nation’s problems.

Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA), then introduced the candidates for Convention President and Vice

President, and asked that they stand as they were named:

The Temporary Convention President allowed the Commissioners a brief moment to consider the

candidates and then asked the Secretary to call the roll. The states were divided between the candidates

and no candidate received a majority of votes. With 12 votes, Rep. Ken Ivory, from Utah was the

leading candidate, followed closely by Dr. John Eastman from California and Rep. Kelly Townsend

from Arizona with 10 votes each.

Rep. Matt Caldwell (FL)

Sen. Gary Daniels (NH)

Dr. John Eastman (CA)

Sen. Alan Hays (FL)

Rep. Ken Ivory (UT)

First-Ever Simulated Convention

of States called to order

September 22, 2016

Sen. Kevin Lundberg (CO)

Mr. Kurt O’Keefe (MI)

Rep. Kelly Townsend (AZ)

Hon. Vance Wilkins (VA)

C

O

N

V

EN

TI

O

N

OP

EN

IN

G

PLEN

A

R

Y

SESSIO

N

6

“Today is the day, the winds

of change are about to blow.”

- Rep. Ken Ivory (UT)

In acts of inspiring statesmanship, several of the nominees voluntarily withdrew their candidacy, and

Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA) encouraged the states to consolidate their votes behind the remaining

nominees. He then ordered the roll a second time. On the second vote, the states were again divided

with Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) receiving a plurality of 17 votes, Dr. Eastman receiving 13, and Rep. Kelly

Townsend (AZ) receiving 11. A murmur ran through the assembly as the Delegations conferred

among themselves and each other.

Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA) again

encouraged the states to consolidate

their votes and again ordered the

roll. On the third vote, Rep. Ken Ivory

(UT) received a majority vote of 28

states and was elected as the

Convention President. Dr. Eastman,

with 12 votes, was elected as the

Convention Vice President.

As Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) took the

podium, he spoke to the body. He

acknowledged the honor that it was to

serve as President before such a group

in such a historic location. He

challenged the body to recognize that

the struggles the nation is facing are not

a product of personnel, but of structure.

The federal government has become a bloated bureaucracy and the states have become almost

powerless. Article V, he urged, is the tool to repair and maintain our federal system of

government. He pled with the Commissioners to act as guardians of the people’s liberty and to work

diligently to that end. Rep. Ken Ivory’s (UT) speech sounded as if it had been lovingly crafted over

a long period of time. Yet it was off the cuff, and from the heart. The man clearly matched the

moment, and the feeling that something special was happening was magnified by his presence at the

podium.

With his exhortation still hanging in the air, Rep. Ken

Ivory (UT) dismissed the Convention to their

Committees and declared the full assembly meeting

adjourned for the day.

State Delegations vote Rep. Ken Ivory

(UT) Convention President

C

O

N

V

EN

TI

O

N

OP

EN

IN

G

PLEN

A

R

Y

SESSIO

N

7

FISCAL RESTRAINTS COMMITTEE

SECRETARY’S SUMMARY

The Fiscal Restraints Committee began with Rep. Bruce Williamson (GA), as temporary Chair pursuant to the

Rules, leading a vote to elect Sen. Kevin Lundberg (CO) as Chair and Rep. Tammie Wilson (AK) as Co-Chair

of the Committee. Commissioners from forty-nine states comprised the Committee, which was tasked with

considering a full docket of amendment proposals involving limitations on taxation and spending and balancing

the federal budget. Professor Robert Natelson was present as a legal advisor and constitutional drafting

consultant.

The first amendment considered under the

subject of balancing the budget was a Debt

Limitation Amendment, which passed by a

wide margin. Under this proposal, the

public debt cannot be increased except

upon a recorded vote of two-thirds of

Congress.

The Committee then moved to the subject

of limiting taxation and spending. The

second proposal adopted by the Committee

was the Fair Tax Amendment, effectively

repealing the 16

th

Amendment and

imposing a national sales tax (the national

sales tax was later stricken by the main

body, as they felt a method of taxation

should not be part of the Constitution but

should instead be enacted legislatively).

This was followed by the narrow passage of a Line Item Veto Amendment proposal (The Line Item Veto

Amendment proposal was later voted down by the main body.

By far, the most time was spent on devising a Balanced Budget Amendment. Commissioners came prepared

for this task with many proposals on how to tackle this complex subject. As possibilities were discussed,

Commissioners such as Sen. Brandt Hershman (IN), who brought extensive fiscal policy experience from their

respective states, weighed in on unintended consequences of wording. Commissioners who are business owners,

such as Bobby Massarini (NY), pointed out that the amendment must be straightforward so that it can be widely

understood by the public. The Chair suggested that a Subcommittee work with Sen. Josh Brecheen (OK), to

hammer out details.

As the Subcommittee returned, the discussion and objections continued. A feeling of disappointment pervaded

the Committee as it realized it would not be able to devise a Balanced Budget Amendment in the short time

allotted to it. Rep. Bill Patmon (OH), a fiscally conservative Democrat, stated that he was committed to staying

late into the night, so determined was he to take something acceptable to his constituents. Statesmanship was

on full display in the Committee room, as Commissioners demonstrated their disdain for disappointing the

constituents they serve.

Vice-Chair Tammie Wilson (AK) put things in perspective for the Committee. She pointed out that although

they could not finish this important amendment in the course of this single day and that they had disagreed on

minor issues, they

had

accomplished a great deal in a very short time. These Commissioners

had

come from all

different states with the common goal of stopping Washington DC from its overreach. She expressed confidence

that with more time in the real Convention, an amendment could certainly be devised that they could agree

upon. She concluded: “Washington should be scared!”

Fiscal Restraints Committee

FI

SC

A

L

R

EST

R

A

IN

TS

C

O

M

M

IT

TEE

8

FEDERAL LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE

JURISDICTION COMMITTEE

SECRETARY’S SUMMARY:

The Federal Legislative and Executive Jurisdiction Committee convened promptly upon adjournment of the

Convention’s Thursday plenary session. The Temporary Committee Chair, Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA),

gaveled the Convention to order and promptly commenced with the Committee’s agenda and ordered the

Secretary to call the roll. The Committee was comprised of Commissioners representing 46 states, 44 of which

were present and ready to proceed with the Committee’s business. Constitutional Scholar Professor Randy

Barnett was also present to act as the Committee’s legal and drafting advisor.

Rep. Buzz Brockway (GA), next proceeded to the election of his replacement, a permanent chair and vice-chair

for the Committee. On the first vote, the Committee was divided with 14 states supporting Sen. Rob Standridge

(OK), 13 supporting Rep. Matt Caldwell (FL), and 16 supporting one of several other candidates. On the second

vote, Sen. Rob Standridge (OK), received a majority and was elected as a Committee Chair with 25 votes. Rep.

Matt Caldwell (FL), as the second highest vote recipient, was elected Committee Vice-Chair with 10 votes.

Notably, throughout the election, Sen. Rob Standridge (OK) abstained from voting and did not cast a ballot in

his own favor, an action which garnered some comments of approval from the other Commissioners.

After a brief address impressing upon the Committee the importance of its task, the Chair opened the floor to

discussion of how the Committee should organize and consider the numerous proposals before it. Initially, there

was no consensus, and the Committee was forced to briefly recess while the Chair and Vice-Chair conferred

over how best to organize the amendment proposals for the Committee’s consideration. Vice-Chair Caldwell

ultimately moved that each of the amendment proposals be grouped into topics and that the Committee should

select the three topics it considered most important. The Committee would then consolidate and consider all of

the amendment proposals under those topics together. On a voice vote, the Committee agreed to this

process. Vice-Chair Caldwell grouped the proposals into 13 separate topics. Through a series of votes, the

Committee narrowed its consideration to three topics: limits on federal rulemaking, limits on Congress’s

Commerce Clause power, and granting the states authority to countermand federal laws. The Committee then

broke into Subcommittees for each topic. Each Subcommittee was charged with consolidating the several

proposals under its topic into a single proposal to be brought back to the body.

The Subcommittee on Rulemaking, as chaired by Sen. Travis Holdman (IN), was tasked with consolidating

seven separate proposals, each of which sought to restrain the growing federal bureaucracy in one way or

another. The Committee ultimately decided on a procedural

check on administrative agencies: Congress could continue

to delegate rulemaking authority to these agencies, but if a

quarter of either House of Congress objected to the rule, a

majority of both Houses would need to vote to affirm the

rule. The Subcommittee noted that Congress frequently

gridlocks on controversial proposals, and so they drafted the

amendment to make it clear that in the event that Congress

does not take any action on a challenged administrative rule,

it is effectively repealed. As one of the Commissioners

noted, Congress shouldn’t be able to pass laws by gridlock,

doing nothing and allowing unelected bureaucrats to do it

for them.

Federal Legislative and Executive

Jurisdiction Subcommittee

FEDE

RAL

LE

GI

SLA

TIVE

& EXE

CUT

IVE

JURI

SDIC

TI

ON CO

M

M

ITT

EE

9

The Subcommittee on the Commerce

Clause was led by Vice-Chair

Caldwell. Despite their disparate

backgrounds, the Commissioners

quickly agreed that Congress’s

Commerce Clause power needed to be

curtailed. This amendment was also

popular among the citizens. Numerous

people had proposed amendments

limiting the Commerce Clause power.

This popular support formed the

backdrop of the Subcommittee’s

deliberations. Of particular concern to

the Subcommittee was ensuring that the

Supreme Court could not simply

reinterpret Congress’s Commerce

Clause as it had in the past. On the

advice of Professor Barnett, the

Subcommittee adopted a two-prong approach. In the first section of the amendment, it affirmatively set forth

what the Commerce Power was intended to be. In the second section, it stated all of the things the Commerce

Power was not, and included language from many of the Supreme Court decisions that had expanded the

Commerce Clause, leaving no room for the Supreme Court to misinterpret or misunderstand the purpose of the

Amendment.

The Subcommittee on Countermand met for the longest time, even as the other Subcommittees were

reconvening into the main body. Under the leadership of Rep. Jim Kasper (ND), the Subcommittee knew it

needed to strike a balance. On one hand, the states needed a constitutional mechanism to push back against

federal abuses of power; on the other, the rule of law needed to be preserved–it would be inappropriate for

states representing a small minority of the population to abrogate federal laws that are supported by the vast

majority of the American people. The Subcommittee debated whether a simple majority of the states should

be able to abrogate federal laws or whether a supermajority should be required. Ultimately, the Subcommittee

opted for a compromise: three-fifths of the states would need to agree in order to abrogate a federal law. This

would ensure that a small minority of the population couldn’t thwart the will of a majority, but would still allow

the states to serve as an instrument of the people when Congress or the Supreme Court implement unpopular

policy.

The Subcommittees went about their work diligently, knowing they had little time to craft these important

amendments. They were so absorbed in their

work that they barely broke for lunch. Instead,

as lunch was carted by, the Commissioners

dashed out into the hallway to make their

selections, and then quickly returned to resume

their discussion. Numerous drafts and revisions

were printed, struck-out, revised, and reprinted. As

an expert in Constitutional Law, Professor

Barnett’s advice was frequently sought, and

many times he found himself needing to be in

three places at once.

In the end, each of the proposals drafted by the

Subcommittees was brought before the entire

Committee for review and approval. Each proposal

met with overwhelming support and was set for

formal introduction to the Convention on the next

day.

Federal Legislative & Executive

Jurisdiction Subcommittee Recess

FEDE

RAL

LE

GI

SLA

TIVE

& EXE

CUT

IVE

JURI

SDIC

TI

ON CO

M

M

ITT

EE

10

TERM LIMITS & FEDERAL JUDICIAL

JURISDICTION COMMITTEE

SECRETARY’S SUMMARY:

The meeting began with the election of the Honorable Vance Wilkins, former Speaker of the House of Virginia,

as Committee Chair. Sen. Alan Hays from Florida was elected as Vice-Chair.

Chairman Wilkins (VA), chose to take up the topic of term limits first. He insisted upon informal debate as

much as possible and suggested the combination of the best possible language from each of the proposals before

the Committee. He moved to have term limits on Congress and term limits on the judiciary separated, and the

body agreed to handle them separately. The Chair then asked the body to review the proposals before them and

prioritize.

The Committee began debate on term limits on Congress. They immediately recognized that term limits were

very popular with the American people, a fact which was reflected the number of terms limits proposals put

forward by the citizens. The debate on term limits lasted for nearly three hours with the Commissioners raising

numerous issues, including the proper number of terms, and whether term limits would only serve to empower

the federal bureaucracies. Several alterations were made to the original proposal through the debate process,

which led to a compromise from all. The final product reflected a wide range of views on the topic, including

the views of some on the Committee who did not support term limits at all.

The Committee turned next to the consideration of limits on the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction. The Committee

decided that it could best represent the people’s wishes by providing a method for vacating Supreme Court

decisions rather than directly reducing the Court’s jurisdiction. There was a general consensus that the people

might find limits on the Supreme Court too controversial. The Committee quickly broke in the middle of its

discussion to grab lunch. A short five minutes later, the Committee was back to their deliberations.

The Chair made the decision to handle the afternoon session in a different manner. He broke up the Committee

into two Subcommittees. One would consider term limits on the Supreme Court, and the other would consider

methods of vacating the Court’s decisions. The Subcommittees split for about one hour to work amongst

themselves and each recommend one proposal back to the entire Committee.

The Subcommittee on Supreme Court Term Limits diverged from any of the initial proposals the Committee

had received. The Subcommittee’s unique proposal left many on the Committee uneasy that a single President

might have the ability to name most of the Court. The Committee itself was sharply divided between those

who favored term limits on the Court and those who favored lifetime appointment. Concerns over giving the

President too much power over the Court ultimately

outweighed concerns about lifetime appointment, and the

Committee rejected the Subcommittee’s proposal.

The Subcommittee on Vacating Supreme Court Decisions

felt there was a deep need to reinvigorate the states’ power

under the Tenth Amendment, which has been effectively

gutted by the Court. The Subcommittee considered a

variety of drafts and ultimately came forward with a

compound proposal that adopted many of the best features

of each. The whole Committee overwhelmingly supported

the proposal and quickly adopted it for a proposal to the

entire Convention.

With its deliberations ended, the Committee adjourned.

Rep. Scott Clem (WY) in Term

Limits & Federal Jurisdiction

Committee

TE

RM

LI

M

IT

S

& F

EDE

RA

L

JU

DICIAL

JURIS

DICT

IO

N

CO

M

M

ITT

EE

11

CONVENTION CLOSING PLENARY SESSION

Prior to the final Plenary Session, the Commissioners attended a breakfast at which they were treated to a speech

by a historian portraying Founding Father, Patrick Henry. Patrick Henry delivered his famous “Give Me

Liberty, or Give Me Death” speech, exhorting the Commissioners to act boldly and bravely as they debated in

the session to come. He set the stage and the mood for what was to be an extraordinary day ahead.

At 9:08 on the morning of September 23rd, as the commissioners trickled in from breakfast, Convention

President Rep. Ken Ivory (UT), gaveled the second plenary session of the Simulated Convention of States to

order. Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) ordered the roll to be called and forty-nine states reported as present, with Kentucky

absent.

The Secretary reported a quorum, and Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) invited Michael Farris to offer the

invocation. Michael Farris prayed for God’s blessings on the proceedings of the day and asked that He preserve

the nation’s heritage of self-governance and liberty.

Upon conclusion of the invocation, Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) led the Convention in the Pledge of Allegiance. Once

again, the air was thick with a feeling of history being made, and an almost indescribable sense of seriousness

reigned. While all knew that this was a simulation, none were treating it as such. They were dealing with our

most precious founding document, and each Commissioner took their role seriously.

Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) asked for a motion

to approve the minutes of the previous

day. The motion was made and seconded

and was adopted by unanimous voice

vote.

Each of the Committee Chairs, Sen.

Kevin Lundberg (CO), Sen. Rob

Standridge (OK), and The Hon.

Vance Wilkins (VA), introduced the

proposals put forward by their

respective Committees (Committee

Reports included on pages 21 through

32) and moved that they be

considered by the body at the

appropriate time. Each of the

Committee Reports was adopted by a

unanimous voice vote of the Convention.

Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) acknowledged the limited time available for consideration of the proposals and urged the

Commissioners to keep their remarks on each proposal brief. With that note in mind, Sen. Kevin Lundberg

(CO) introduced the first proposal of the Fiscal Restraints Committee:

SECTION 1.

The public debt shall not be increased except upon a recorded vote of two-thirds of

each house of Congress, and only for a period not to exceed one year.

SECTION 2

. No state or any subdivision thereof shall be compelled or coerced by Congress or the

President to appropriate money.

SECTION 3.

The provisions of the first section of this amendment shall take effect three years

after ratification.

CONVENT

ION

CL

O

SING P

LE

NARY

SES

SION

12

Debate ensued, with the Commissioners

proceeding to dissect the language of the proposed

amendment. Commissioners questioned whether

“compelled or coerced” was the appropriate

language and suggested “required” might be more

straightforward and to the point. One

Commissioner suggested that perhaps Section 2

should apply to Congress, the President, and the

Federal Judiciary, not just Congress and the

President. But this raised concerns that it might

make it impossible to enforce contracts with the

state governments. Ultimately, the Convention

simply decided to adopt the language as

proposed. On a roll call vote, the debt limitation

amendment passed overwhelmingly: 45 to 3.

Next, Rep. Matt Caldwell (FL) introduced the first proposal of the Federal Legislative and Executive

Jurisdiction Committee:

SECTION 1

. The power of Congress to regulate commerce among the several states shall be

limited to the regulation of the sale, shipment, transportation, or any movement of goods, articles

or persons. Congress may not regulate activity solely because it affects commerce among the

several states.

SECTION 2

. The power of Congress to make all laws that are necessary and proper to regulate

commerce among the several states, or with foreign nations, shall not be construed to include the

power to regulate or prohibit any activity that is confined within a single state regardless of its

effects outside the state, whether it employs instrumentalities therefrom, or whether its regulation

or prohibition is part of a comprehensive regulatory scheme; but Congress shall have the power to

define and provide for punishment of offenses constituting acts of war or violent insurrection

against the United States.

SECTION 3

. State legislatures shall have the standing to file any claim alleging a violation of this

article. Nothing in this article shall be construed to limit standing that may otherwise exist for a

person.

SECTION 4

. This article shall be effective not more than five years from the date of its ratification.

In debate, concerns were raised that Section 4 could be read to mean that the amendment would only be in

effect for five years, rather than going into effect after five years, which was the clear intent of the

Committee. The Convention addressed the issue by changing Section 4 to read “This article shall become

effective five years from the date of its ratification.” With this minor change, the Commerce Clause Limitation

Amendment also passed overwhelmingly: 44 to 6.

Sen. Alan Hays (FL), introduced the first proposal of the Term Limits and Federal Judicial Jurisdiction

Committee:

No person shall be elected to more than six full terms in the House of Representatives. No person

shall be elected to more than two full terms in the Senate. These limits shall include the time served

prior to the enactment of this Article.

This Term Limits Amendment was hotly contested in debate. A number of Commissioners raised concerns

that imposing term limits would only empower the federal bureaucracy since they are permanently in office and

can simply outlast adverse Congresses by waiting for them to term out. Objections were also raised that term

CONVENT

ION

CL

O

SING P

LE

NARY

SES

SION

13

limits effectively limit people’s choice in elections–if people don’t want their Congressmen serving lengthy

terms they can just vote them out. Proponents of the proposed amendment countered that term limits are

necessary to overcome the advantage that incumbents have in virtually every election and that term limits

empower the people by getting fresh faces into office. An effort was briefly made to compromise by extending

the term limits in the proposal from six to nine in the House and two to three in the Senate, but that change was

ultimately rejected. When the Term Limits Amendment was finally put to a vote it passed 35 to 12.

Rep. Mark Lepak (OK) introduced the second proposal from the Term Limits and Federal Judicial Jurisdiction

Committee:

SECTION 1

. Any decision of the Supreme Court may be vacated by a resolution passed by the

legislatures of three-fifths of the several states or by two-thirds of both houses of Congress. No

state legislative resolution older than five years shall be counted to aggregate the necessary number.

SECTION 2

. A decision that is

vacated within six months of the date

of the entry of the judgment shall

result in a vacation of the judgment

itself. Otherwise, a decision vacated as

provided herein shall not disturb the

judgment as between the named

parties.

SECTION 3

. The congressional

override is not subject to a presidential

veto and shall not be the subject of

litigation or review in any Federal or

State court.

SECTION 4

. The states’ override

shall not be the subject of litigation or

review in any Federal or State court, or oversight or interference by Congress or the President.

Substantial debate immediately arose over the text of the Judicial Override Amendment, largely over whether

Congress should be given the power to override Supreme Court decisions. An effort to amend the text raised

several other issues, and it became clear that more work was needed to clean up the text of the proposal. The

Convention decided to postpone discussion on the Judicial Override Amendment until after lunch so as to allow

the Committee to refine the language and bring forward a clean proposal.

With discussion of the previous amendment postponed, Rep. Jim Kasper (ND) introduced the second proposal

from the Federal Legislative and Executive Jurisdiction Committee:

SECTION 1:

The States shall have authority to abrogate any provision of federal law issued by

the Congress, President, or Administrative Agencies of the United States, whether in the form of a

statute, decree, order, regulation, rule, opinion, decision, or any other form.

SECTION 2:

Such abrogation shall be effective when the legislatures of three-fifths of the States

approve a resolution declaring the same provision or provisions of federal law to be abrogated. This

abrogation authority may be applied to provisions of federal law existing at the time this

amendment is ratified.

SECTION 3:

No government entity or official, whether federal, state, or local, may take any action

to enforce a provision of federal law after it is abrogated according to this Amendment. Any action

to enforce a provision of abrogated federal law may be enjoined by a federal or state court of general

CONVENT

ION

CL

O

SING P

LE

NARY

SES

SION

14

jurisdiction in the state where the enforcement action occurs, and costs and attorney fees of such

injunction shall be awarded against the entity or official attempting to enforce the abrogated

provision.

SECTION 4

. No provision of federal law abrogated pursuant to this Amendment may be reenacted

or reissued for six years from the date of the abrogation.

The debate focused almost entirely on making minor tweaks to the language. With several small changes

having been made, the Abrogation Amendment passed 43 to 5.

Thanking the Commissioners for their hard work, Rep. Ken Ivory (UT) dismissed the body for a short lunch

recess. Over lunch, the Federal Term Limits and Judicial Jurisdiction Committee continued to meet to refine

the language of their Judicial Override Amendment.

When the Convention returned from lunch, Rep. Mark Lepak (OK) reintroduced the Judicial Override

Amendment with the changes made by the Committee over lunch:

SECTION 1:

Any decision of the Supreme

Court invalidating a state law may be

vacated, and the law reinstated, by a

resolution passed by the legislatures of three-

fifths of the several states or by two-thirds of

both houses of Congress. No state legislative

resolution older than five years shall be

counted to aggregate the necessary number.

SECTION 2:

A decision vacated as provided

herein shall not disturb the judgment as

between the named parties.

SECTION 3:

The Congressional override is

not subject to a Presidential veto and shall not

be the subject of litigation or review in any

Federal or State court.

SECTION 4:

The States’ override shall not

be the subject of litigation or review in any

Federal or State court, or oversight or

interference by Congress or the President.

The debate continued where it had left off, with several Commissioners raising questions about the text of the

proposal. Other Commissioners were concerned that providing the states the ability to override the Federal

Judiciary went too far and gave the states too much power. The general consensus among the body seemed to

be that while the concept of a judicial override was solid in theory, more time was needed to refine the text of