To view this on the COS website, click here co-document-library-case-for-series-part-5

To download the pdf file from the COS website, click here 5._Case_for_State_Convention_and_Colorado_Ratifying_Plan_(as_of_February_17%%__%%2025)_v1.5.pdf

CO Document Library-Case for Series Part 5

Attachment: 4673/5.CaseforStateConventionandColoradoRatifyingPlan(asofFebruary17__2025)v1.5.pdf

|

1

Case for State Convention Mode of

Ratification for Amendments to the U.S.

Constitution

A Colorado Ratifying Plan and other evidence to support a State Convention

Written by Mr. Michael D. Forbis

Version 1.5 (as of February 17, 2025)

Purpose. To socialize the idea of a state level ratifying convention following an Article V

“Convention for proposing Amendments.” A Colorado Ratifying Convention is the example

used within this document. This is a living document, and it can be updated and improved from

new lessons learned.

Disclaimer. The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily

represent the views of Convention of States Action (COSA), its staff, or affiliates.

2

Executive Summary

In Article V of the U.S. Constitution, there are two modes of ratification for proposed

amendments, and they are by state legislatures and state level conventions. There are several

advantages for conducting a state level ratifying convention for proposed amendments to the

U.S. Constitution.

•

The state convention method can more directly involve grassroot citizens in the

amendment process, and it is a better reflection of the people’s will. The

Colorado

Ratifying Plan

explains the conceptual idea of the process.

•

A state convention method is twice as likely to be successful to ratify amendments as the

state legislature method.

1

•

Voters will likely trust a state convention more than the state legislature to examine

proposed amendments.

2

•

There is greater certainty the outcome of a state convention will remain unchanged than a

state legislature.

3

•

There is less bias with the state convention method because it has a greater chance of

involving direct “independent” voters.

4

The mode of ratification by state convention is a method to bypass a state legislature just

as an Article V “Convention for proposing Amendments” is a method to bypass Congress. They

both represent a constitutionally based approach for grassroot citizens to bypass their elected

leaders to address amendments to the U.S. Constitution, and they resemble the best opportunities

for grassroot citizens to become involved in self-government. When an Article V Convention

meets to propose amendments, it will be a historical opportunity and will likely have nationwide

attention drawn to it. To maintain the momentum of grassroots activism started through an

Article V Convention, it makes sense for it to continue through state level ratifying conventions.

The content of this case paper provides additional evidence and support for a state

convention as the better mode of ratification for amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

1

See Appendix A, page A-1 (mathematical model using Law of Total Probability)

2

See Appendix A, page A-2 (recent polling research from national and state organizations)

3

See Appendix A, pages A-3 to A-6 (historical record examination on both modes of ratification)

4

See Appendix B, pages B-1 to B-4 (statistical hypothesis test)

3

Colorado Ratifying Plan

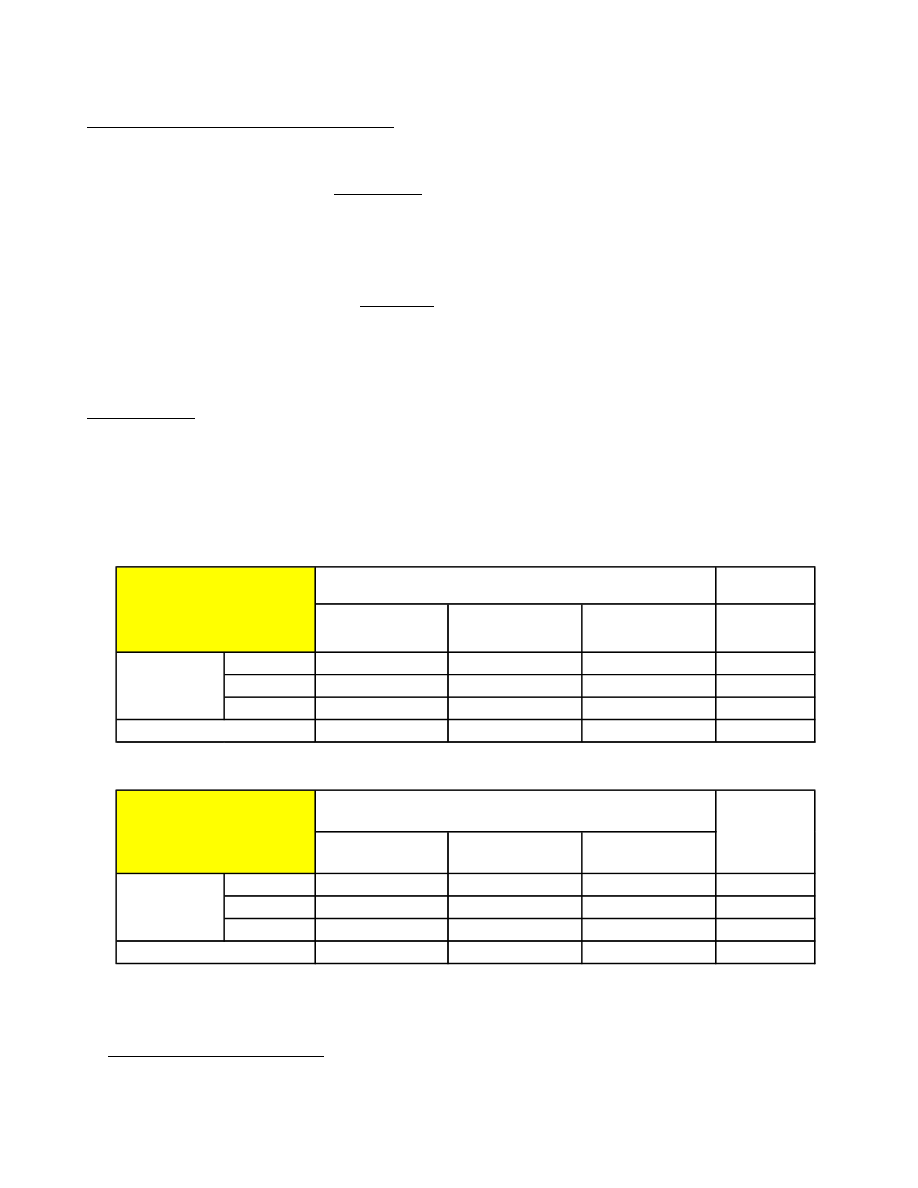

Prior to ratification, amendments must first be proposed. An Article V Convention is an

alternative approach to proposing amendments to the U.S. Constitution rather than the U.S.

Congress. Even though there is no specific historical precedent of an Article V Convention,

there is general historical precedent for conventions such as the 1787 Philadelphia Convention.

For the purposes of this “Colorado Ratifying Plan,” the assumption is an Article V Convention

successfully proposed written amendments. In addition, there is the assumption of a reasonable

timeframe for ratification, and the mode of ratification is by state level convention.

5

Based on

these assumptions, the preparation and execution of a Colorado Ratifying Convention can follow

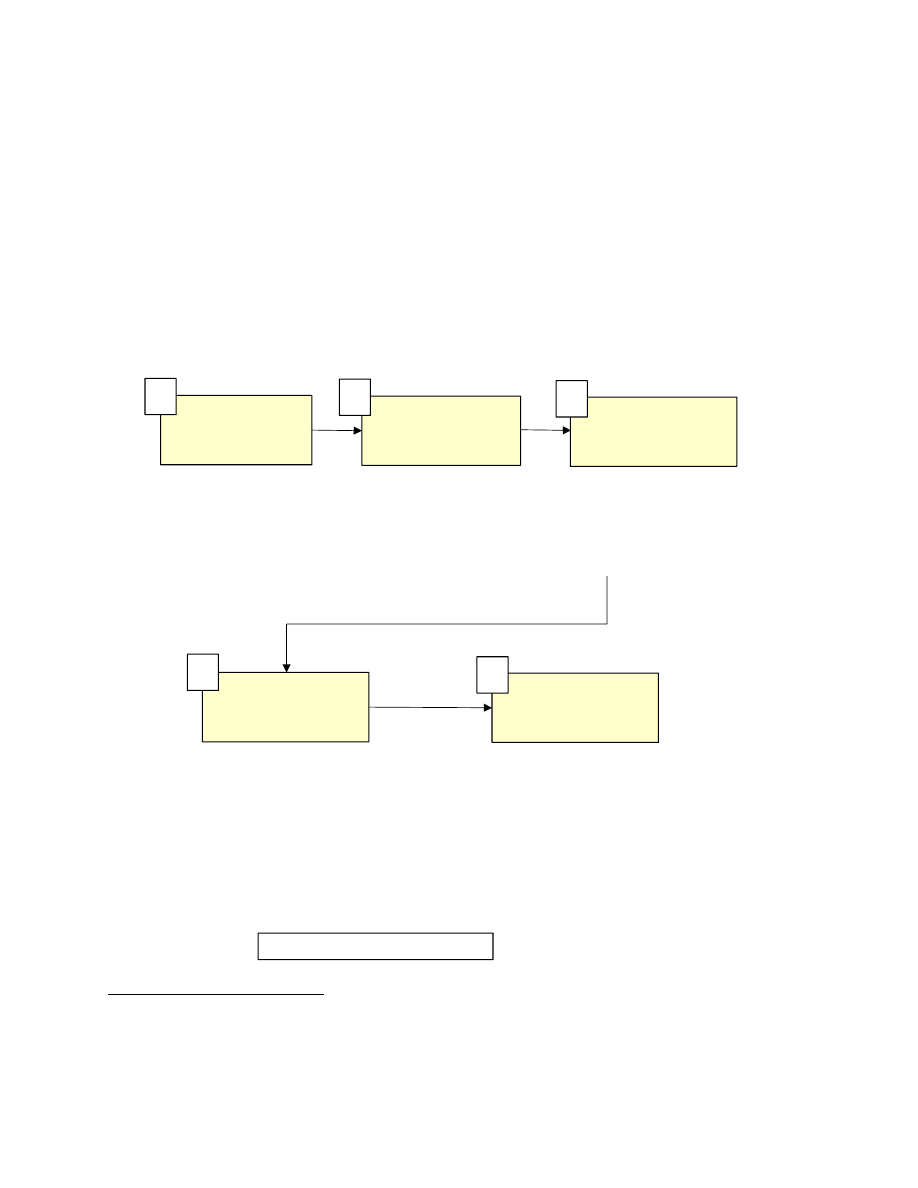

the general process depicted in Figure 1.

5

Appendix C (Historical Ratification of Amendments) explains some historical background and track record of the 33 proposed

amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It provides specific case examples of 10 proposed amendments with the timeframe of

ratification set by Congress of seven years, and it provides sample languages to include within the

amendment text

involving

timeframe of ratification and mode of ratification. This historical examination into the ratification of U.S. Constitution

Amendments is critical background for consideration in an Article V Convention and Colorado Ratifying Convention.

Article V

Convention

•

5-8 Proposed

Amendments

•

Timeframe for

Ratification: 7 years

•

Mode of Ratification:

State Convention

(recommendation)

Colorado

Statute Passed

•

Set dates and location

for convention

•

Establish election

procedure for

convention delegates

U.S. Congress

Review

•

Review proposed

amendments;

ensure consistency

with commission

•

Send to state

conventions for

ratification

Statewide

Election

•

100s of eligible citizens

register in each Colorado

Senate District (SD)

•

Five citizens from each SD

randomly chosen

•

Voters select 1 of 5 citizens

on ballot to become delegate

•

Total of 35 delegates voted to

convention

State

Convention

•

~Two Weeks in Duration

•

Follow Mason’s Manual of

Legislative Procedures

•

Elect Convention Leadership

•

Examine 5-8 Proposed

Amendments

•

18 of 35 Delegates needed to

ratify a single amendment

•

Vote on each amendment

separately

1

2

3

4

5

Figure 1: Colorado Ratification Process

4

In this particular scenario, the Article V Convention is likely to propose between 5-8

amendments to the U.S. Constitution, and this range is a reasonable planning assumption. The

proposed amendments are within the parameters of Article V Convention’s 3-part platform.

•

Impose fiscal restraints on the federal government

•

Limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government

•

Limit the terms of office for federal officials and for members of Congress

In addition, the Article V Convention is successful in establishing a mode of ratification by state

level convention with a timeframe for ratification of seven years.

6

Upon receipt of the proposed

amendments, the U.S. Congress conducts a review to ensure the proposed amendments are not

outside the parameters of the Article V Convention’s 3-part platform. For example, the proposed

amendments cannot address anything related to individual liberties and rights, and this subject

area is clearly outside the main scale and scope of the convention to “limit the power of the

federal government.” Once reviewed, the U.S. Congress determines the mode of ratification by

state convention (assumed as a recommendation by Article V Convention) and sends the

proposed amendments to the states for ratification.

Unlike an Article V Convention, there is specific historical precedent for state level

ratifying conventions, and the 21

st

Amendment is the only one to be ratified by state level

conventions. The 21

st

Amendment was the repeal of the 18

th

Amendment, and it delegated to the

states to determine any limitations / prohibition of alcohol. In the 1932 general election, there

was a national mood from both Republicans and Democrats to repeal the 18

th

Amendment. Most

importantly, both parties agreed that Congress should adapt an amendment to repeal the 18

th

Amendment, and it should be sent to the states for ratification by state level conventions.

7

The

overall result of state level conventions was that they

“truly registered the will of the American

people on a great national issue.”

8

Similarly, state level conventions will also capture the true

will of the American people on the current day national issue to “limit the power of the federal

government.” When an Article V Convention meets, it is very likely to be on the national scene

as a unique historical event, and state level ratifying conventions are very appropriate to close

out this overall historical movement.

Once Colorado receives the proposed amendments, it needs to pass a statute for the state

ratifying convention time and location, and the statute will explain the election process for

delegates to the convention.

9

In 1933, Colorado passed a statute to form a state level convention

6

See Appendix C. With the exception of the 27

th

Amendment, all amendments to the U.S. Constitution were ratified well under

7 years, and this is a reasonable timeframe (i.e., includes group of 10 amendments - Bill of Rights). There are two historical

examples of proposed amendments that did not ratify within seven years (Equal Rights Amendment (1972) and DC Voting

Rights Amendment (1978). There is enough historical precedent of ratification success within seven years versus not.

7

Ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States: State Convention Records and Laws

,

Compiled by Edward Somerville, 1939, pages 3-4 (Introduction).

8

Ratification of Twenty-First Amendment

, page 8.

9

Note. The qualifications for state delegates can reference the published qualifications for commissioners sent from Colorado to

the original Article V Convention. Thus, it can be an easy copy and paste from already approved qualifications.

5

for the 21

st

Amendment. In the statute, the governor nominated 30 candidates who were regular

citizens of the state, and there was a statewide election for Colorado voters to select 15 of them

as official delegates to the state convention. In addition, the statute determined the location of

the convention was in the Colorado Senate Chamber, and it was scheduled September 26, 1933.

Finally, the statute provided general instructions for how citizens would use a ballot vote.

10

For

the Article V Convention proposed amendments, Colorado can pass a statute like the 21

st

Amendment with some differences. The statute should designate the Colorado Senate Chamber

as the location of the state convention, and it should explain that

Mason’s Manual for Legislative

Procedure

will serve as the governing rules for the convention.

11

In addition, the statute should

explain how one delegate will come from each of the 35 Senate Districts in the state in order to

provide a fair representation from across Colorado, and the basis for using 35 Senate Districts to

determine delegates originates from the Colorado Constitution.

12

As compared to the 21

st

Amendment, 35 delegates are significantly greater than 15 delegates, and the statute should not

allow a role for the governor in the delegate election process because the governor does not have

a role in the state application for the original Article V Convention. It is critical to remember

that Article V of the U.S. Constitution does not allow for an “executive branch” role in the

amendment process by either the President of the United States or State Governors.

For the actual statewide election as described in the statute, Colorado citizens can

volunteer to be a delegate and must file to be a delegate within their respective Senate District. It

is likely that hundreds of citizen volunteers will file to be a delegate within each Senate District,

and there will be a deadline to file. After filing, a random selection of five individuals from the

hundreds who filed will take place for each Senate District, and these five individuals will be

candidates for their respective Senate District as a delegate in a statewide election. Each

candidate will not necessarily need to campaign to become a delegate, but they will submit a

short summary of their qualifications and desire to be a delegate to the state level ratifying

convention. Afterwards, voters in each Senate District can review the five candidates, and voters

will eventually choose one of the five candidates to be a delegate during the statewide election.

As a result, there will be 35 total delegates elected to the state ratifying convention. Through this

election process, there are three components involving volunteering, random selection, and

choice, and all three components combined provide a fair and balanced approach for determining

delegates. It helps to reduce “bias,” and it helps to ensure greater chances for “independent”

voters to be included within the state ratifying convention instead of typical Democrat and

10

Ratification of Twenty-First Amendment

, pages 535-538.

11

Colorado Legislative Rules

, Legislative Council Publication 816, Updated November 2024, Senate Rule 40 (Parliamentary

Authority). Explains the latest edition of

Mason Manual of Legislative Procedure

shall govern the Senate in all cases in which it

is not inconsistent with the rest of the Colorado Legislative Rules.

12

Section 1, Article XIX (Amendments) of the Colorado Constitution published in 1876 discusses how to call a Colorado

Convention for amending the Colorado Constitution. It explains how delegates will be elected from each of the Senate Districts

established in Colorado. It is practical to apply this general rule from the Colorado Constitution to elect delegates from each of

the 35 Colorado Senate Districts for a Colorado Ratifying Convention for proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

6

Republican minded individuals.

13

Finally, Colorado has historically conducted statewide voting

to determine the final version of amendments added to the Colorado Constitution whether they

originated from ballot initiatives or legislative referrals. In either case, the final approval for any

Colorado Constitutional Amendment was determined by the people of Colorado. Thus, this

election process for determining delegates for the Colorado Ratifying Convention for U.S.

Constitutional Amendments ensures a level of consistency with the Colorado historical practice

of gaining the people’s approval.

14

After the election process, the 35 delegates will meet in the Colorado State Senate

Chamber for the Colorado Ratifying Convention. During the Colorado state convention for the

21

st

Amendment, the 15 delegates elected a President of the Convention and other convention

officials such as a committee chair. In addition, the convention delegates took their oath of

office, established convention procedures, and a voting rule (8 of 15 delegates) for ratification.

There was debate on the 21

st

Amendment and its impact on Colorado. At the conclusion of the

convention, there was a full vote of 15-0 to ratify the amendment. Overall, the convention was

90 minutes in length, and Colorado became the 24

th

state to ratify the 21

st

Amendment on

September 26, 1933.

15

In all the state ratifying conventions in the United States, the entire length

of time did not exceed a day, and New Hampshire posted the shortest recorded convention of 17

minutes long.

16

In addition, the state conventions to ratify the base U.S. Constitution from 1787-

1788 ranged from 4-38 days in length.

17

For the 5-8 proposed amendments from the Article V

Convention, a Colorado Ratifying Convention will need approximately two weeks. It will

already have established rules to follow from

Mason’s Manual of Legislative Procedure

, and the

first couple of days of the convention can be used to review the rules, elect convention officials,

and establish any appropriate committees (e.g., three committees aligned to 3-part platform of

the Article V Convention). The actual reading of the 5-8 proposed amendments will be straight

forward because they should be short (<350 words each), and delegates can only vote to ratify

the amendment as written or not. There are no edits permitted to adjust the language of the

proposed amendments. Thus, it is very likely the vast majority of time spent by delegates is

discussing, understanding, and debating any merits to each amendment. In many ways, the

Colorado Ratifying Convention will be less complex than the Article V Convention to propose

amendments. It is possible for committees to spend 2-3 days discussing their respective assigned

amendments to examine, and then the main convention plenary of all 35 delegates could spend

an entire 2

nd

week to debate any of the merits of the proposed amendments. At the end, the 35

delegates cast individual votes (18 of 35 voting rule) for each amendment independently, and the

13

Appendix B (Statistical Hypothesis Test in Support of State Convention) provides statistical evidence for how “independent”

voters are significantly less “bias” than Democrat and Republican voters.

14

The Colorado Constitution has been amended 166 times as of 2023, and all these were finally approved by a statewide vote

from Colorado citizens. Thus, the practice for gaining the people’s approval for changes to the Colorado Constitution is a strong

historical precedent, and this should continue for ratifying proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

15

Ratification of Twenty-First Amendment

, pages 33-42. Note: Utah became the 36

th

state to ratify the 21

st

Amendment on

December 5, 1933 for it to become effective.

16

Ratification of Twenty-First Amendment

, page 7.

17

Appendix A summarizes the state conventions that ratified the base U.S. Constitution from 1787-1788.

7

convention concludes with all amendments ratified or some of them ratified. Essentially, the

Colorado Ratifying Convention serves much like a legislative body, but it is not as complicated

to conduct as either the Colorado House of Representatives or Senate. Its sole purpose is to read,

debate, and vote on a series of 5-8 proposed amendments that amount to probably no more than

3-pages total of complete written text, and they should be simple and straight forward to

understand. Since no editing is allowed, the Colorado Ratifying Convention will have an easier

time with implementing it legislative procedures and rules to follow. Most importantly, typical

Colorado citizens can be successful delegates to the Colorado Ratifying Convention with little to

no experience in legislative affairs.

This “Colorado Ratifying Plan” is intended to be a conceptual plan to help lay the

foundation for a more detailed plan for a Colorado Ratifying Convention, and it is intended to

socialize the general idea of a state convention.

The background and historical references offer

additional information for the detailed plan development as well. A Colorado Ratifying

Convention is better to examine the proposed amendments than the Colorado State Legislature

because it will not be distracted by other legislative priorities. In addition, it will be less

bias

than the Colorado State Legislature because it will have direct “independent” voters present

without being entirely occupied by Democrats and Republicans. Finally, and most importantly, a

Colorado Ratifying Convention will truly be a reflection of Colorado citizens and their will for

the state.

Supporting Appendices (other evidence to support a state convention)

•

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention (A-1 to A-6)

•

Appendix B: Statistical Hypothesis Test in Support of State Convention (B-1 to B-4)

•

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments (C-1 to C-6)

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention

A-1

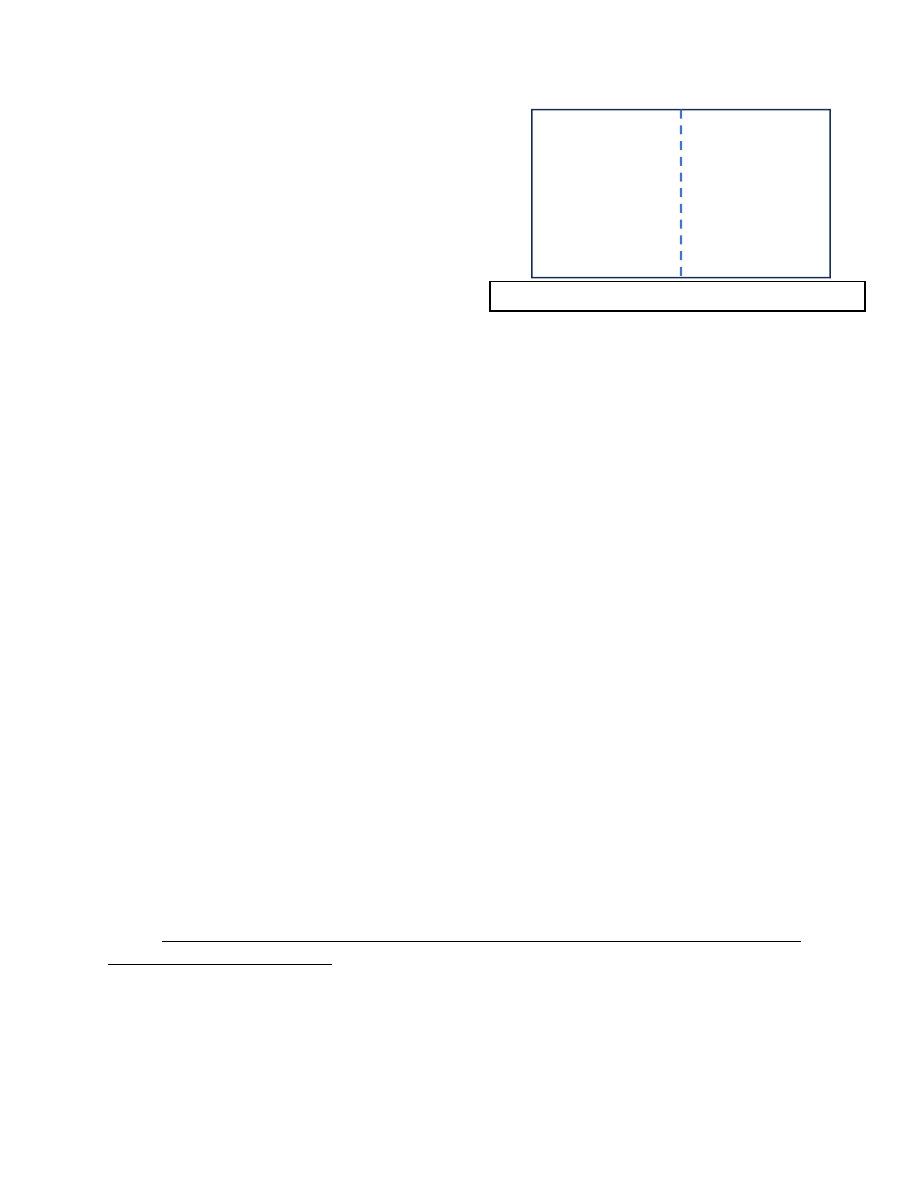

The two different modes of ratification within

Article V of the U.S. Constitution can be compared

using the Law of Total Probability. The law basically

states that mutually exclusive events within the same

universal set equal to a total probability of one (1.0). In

the case of Figure 2, the binary probabilities (Pr) of

success and failure of a single event have a total sum

probability of 1.0, and it can be represented in the

following equation: Pr(S) + Pr(F) = 1.0

Article V states that “three fourths of the several States” (38 of 50) must ratify an

amendment for it to become effective. Another way to view this Article V requirement is that it

takes 13 of 50 states to vote against an amendment for it not to become effective, and this inverse

rule applies differently to the two different modes of ratification.

For the state legislature mode of ratification, there are 99 General Assembly state

chambers (or 99 unique legislative bodies) that may examine a proposed amendment. Nebraska

is the only state with one chamber (Senate), and the other 49 states have two chambers (House

and Senate). In those states with two chambers, both are required to pass a proposed amendment

in order for the whole one state vote to ratify the proposed amendment. On the other hand, it

only takes a single chamber to vote against a proposed amendment for the whole one state vote

to be against the amendment. Essentially, it takes 13 of 99 state chambers to vote against a

proposed amendment for it not to become effective at all. The overall probability of success

using the state legislature mode of ratification is represented by the following equations below.

•

Calculate Failure Rate: (99-13)/99 = 86/99 = 0.869 = Pr(F)

•

Probability of Success: Pr(S) = 1-Pr(F) = 1-0.869 = 0.131 or

13.1%

For the convention mode of ratification, there are 50 single state conventions (or 50

unique legislative bodies) that may examine a proposed amendment. The result of each

convention counts as the whole one state vote to ratify or not ratify the proposed amendment. It

takes 38 of 50 state conventions to ratify a proposed amendment for it to become effective. On

the other hand, it takes 13 of 50 state conventions to vote against a proposed amendment for it

not to become effective at all. The overall probability of success using the convention mode of

ratification is represented by the following equations below.

•

Calculate Failure Rate: (50-13)/50 = 37/50 = 0.74 = Pr(F)

•

Probability of Success: Pr(S) = 1-Pr(F) = 1-0.74 = 0.26 or

26%

Therefore, the convention method is twice as likely to be successful to ratify amendments

as the state legislature method.

This basic mathematical model using the Law of Total

Probability makes a simple case for why the convention method should be the preferred mode of

ratification, and it assumes full participation by all states in the ratification process (i.e., no state

is “dormant” from participating).

Success (S)

Failure (F)

Figure 2: Basic Venn Diagram for Mutually Exclusive Outcomes

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention

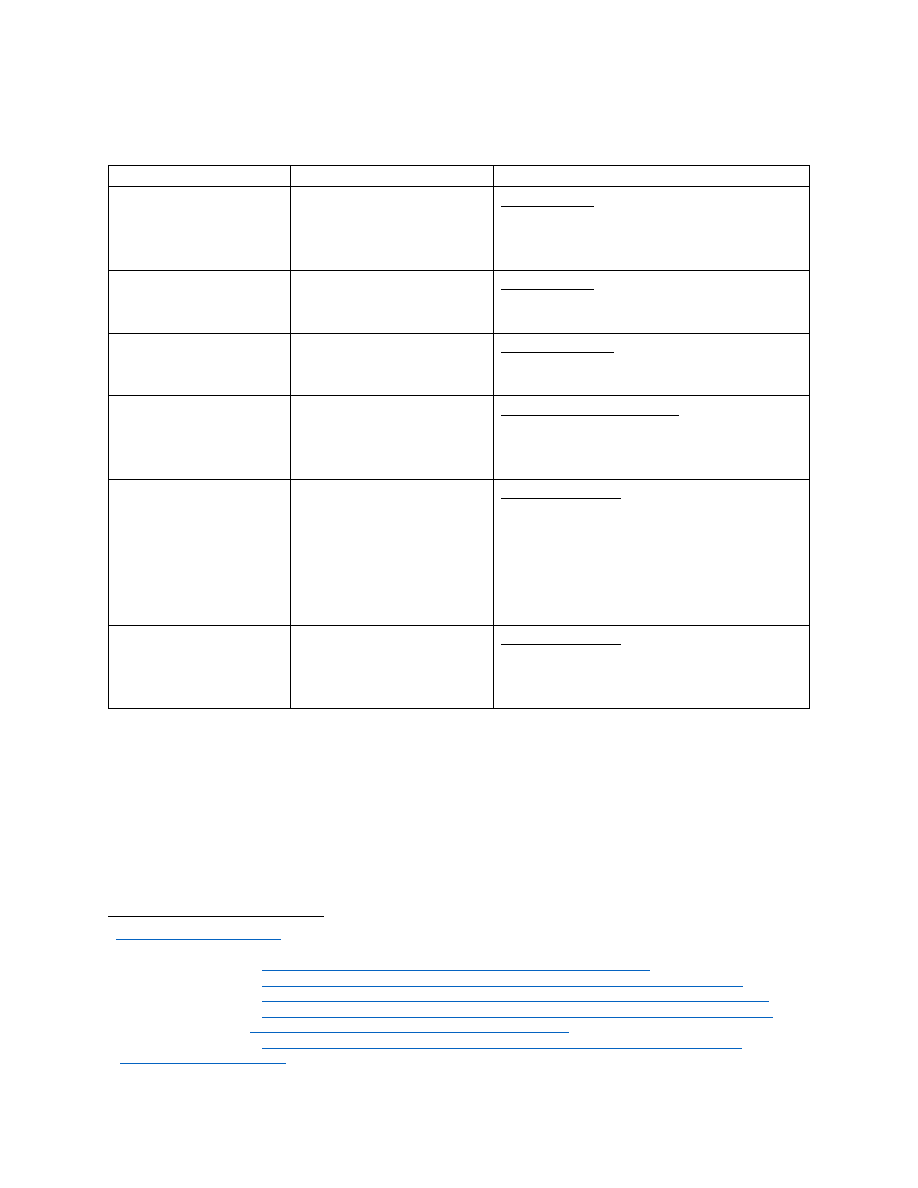

A-2

In a nation-wide poll conducted by Susquehanna Polling and Research (SB&R) in August

2024, the following question was asked: “Who do you trust more – the state legislators who live

and work closer to your home, or Members of Congress who live and work in Washington,

D.C.?” The response was 59% state legislators and 8% Members of Congress.

1

However, this

survey compares two entities within the same compound question, and the better comparison is

through two independent questions as shown Figure 3 (two pie charts). In reality, the level of

trust in the federal government is about 20-25% over the last 15 years,

2

and it is the same level of

trust for Colorado. In

Colorado, the level of trust in

the state government is 37%,

and this likely applies to the

state legislature.

3

The trend

is that voters trust people

closer to home, and a state

convention represents people

closer to home.

Thus, voters

will likely trust a state

convention more than the

state legislature to examine

proposed amendments

.

1

https://conventionofstates.com/national-polling-shows-massive-support-for-limiting-federal-power-and-an-article-v-convention

2

Pew Research Center:

https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/

3

Colorado Polling Institute (CPI), Survey of Likely Voters, November 28, 2023 (slide 23)

https:%%//%%static1.squarespace.com/static/645aadf3ccf9412509fbc4a7/t/65781eb1e7162d4ef9e53a26/1702371000883/21136+CPI-\\ CO-Deck_v2-CO-issues.pdf

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

19

58

19

66

19

70

19

74

19

77

19

79

19

82

19

85

19

87

19

89

19

91

19

93

19

95

19

97

19

98

20

00

20

02

20

04

20

06

20

08

20

10

20

12

20

14

20

17

20

20

20

22

20

24

National Survey Question: Do you trust the federal government to do

what is right?

(% Responses: Just about always or most of the time)

(Pew Research Center)

20-25% Level of Trust

After 9/11 Attacks

Trust a lot

7%

Trust a little

18%

Neither trust

nor distrust

13%

Unsure

1%

Distrust a little

19%

Distrust a lot

42%

Survey Question for Colorado: How much do you trust or

distrust the

Federal Government

to do the right thing?

(Colorado Polling Institute (CPI), November 2023)

25% Level of Trust

Figure 3: Polling Summaries

Trust a lot

12%

Trust a little

25%

Neither trust

nor distrust

16%

Unsure

2%

Distrust a little

19%

Distrust a lot

26%

Survey Question for Colorado: How much do you trust or

distrust the

Colorado State Government

to do the right thing?

(Colorado Polling Institute (CPI), November 2023)

37% Level of Trust

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention

A-3

According to historical record, the state legislature was the mode of ratification for 26 of

27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution, and the state convention was the mode of ratification

for the base Constitution (1787-1788) and 21

st

Amendment (1933). In general, both have

demonstrated to be successful modes of ratification. However, there are some historical cases

where states changed their original decision, and it caused uncertainty in the overall amendment

process.

From 1866-1867, New Jersey and Ohio were some of the early states to ratify the 14

th

Amendment, yet they later rescinded their decision. In addition, North Carolina, South Carolina,

and Georgia initially rejected the 14

th

Amendment, yet they later ratified the 14

th

Amendment

under their new reconstructed state legislatures (i.e., based on Reconstruction Act). Secretary of

State William Seward informed Congress of the situation explaining the inclusion of these 5

states makes up 28 of 37 required to ratify the 14

th

Amendment. The U.S. Congress declared the

14

th

Amendment was ratified by a Joint Resolution passed in July 1868.

4

Thus, Congress set the

historical precedent to recognize only the first ratification decision by New Jersey and Ohio but

not the rescissions. On the other hand, Congress also recognized the changed decisions to ratify

the 14

th

Amendment by North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. This historical example of

the 14

th

Amendment is the only one to have a successful overall ratification that depended on

states that initially rejected it but later ratified it. There are other amendments where states

initially rejected it but later ratified it. However, the changes came after final passage was

complete, or there were more than enough states to ratify it without the changes. In other words,

the states who changed from an initial rejection to ratification did not make a difference in the

final passage of the amendment. In another instance, New York ratified the 15

th

Amendment and

later rejected it, yet the U.S. Congress declared the ratification of the 15

th

Amendment counting

New York’s first decision of ratification and not the rescission.

5

In these examples, the state

legislature was the mode of ratification, and there was no time limit for these amendments.

When it comes to the rescissions of previous ratifications by state legislatures, Article V of the

Constitution only addresses states’ power to ratify an amendment and not rescissions.

6

These

case examples of the 14

th

and 15

th

Amendments support this precedent by Congress.

In a century later, the precedent to not recognize rescissions by the state legislatures

would come into question during the ratification process of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

proposed by Congress in 1972. The ERA had a time limit of seven years, and 35 states initially

ratified the amendment when 38 were required. Five of the original states (Kentucky, Nebraska,

Tennessee, Idaho, and South Dakota) later rescinded their original ratifications within the seven

year timeframe, and Congress did not recognize these rescissions when it extended the time limit

for another three years. In the case

Idaho v. Freeman

(1982), the federal district court concluded

the state rescissions should be recognized, and it stated Congress could not change the deadline

once established in 1972. In an appeal to the Supreme Court, the federal district court was

instructed to dismiss the case as moot because the 2

nd

deadline set by Congress had expired with

4

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42979,

The Proposed Equal Rights

Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues

, December 23, 2019, p.21

5

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42979,

The Proposed Equal Rights

Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues

, December 23, 2019, p.21

6

https://www.equalrightsamendment.org/pathstoratification

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention

A-4

no additional states who ratified the amendment.

7

So, the rescissions of these five states were

initially recognized as valid by the federal district court, and it could come into question again

with future proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution with a mode of ratification by state

legislatures.

When it comes to the powers of state legislatures under Article V of the U.S.

Constitution, there are numerous historical examples where state legislatures passed an

“Application” to call a “Convention for proposing Amendments,” and some state legislatures

later rescinded their application.

8

In these circumstances under Article V, the U.S. Congress

recognized the state legislatures rescissions in every case, but Article V of the Constitution only

addresses states’ power to make an “Application” for a convention and not rescissions. In other

words, Congress recognizes one form of rescission under Article V but not the other form.

Unfortunately, there is a potential inconsistency by Congress with regards to state legislatures

changing an original decision under Article V. Therefore, state legislatures should examine their

original decision on an amendment very carefully and make it final, and this approach avoids the

uncertainty on the overall outcome of an amendment that may result from state legislatures

changing their original decision.

In the U.S. Constitution, Article VII says “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine

States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so

ratifying the Same.” Essentially, Article VII stated the mode of ratification of the base

Constitution was by state convention, and it only addresses states’ power to ratify and not rescind

(similar to Article V). The table below summarizes the historical record of state conventions,

and the length of time ranged 4-38 days (excluding Rhode Island).

9

By the time George

Washington was sworn in as the First President of the United States, there were 11 states that

ratified the Constitution with the exception of North Carolina and Rhode Island.

States

Timeframe for State Convention

Vote Count (# delegates)

Delaware

December 4-7, 1787 (4 days)

30-0 (30)

Pennsylvania

November 20 – December 12, 1787 (23 days)

46-23 (69)

New Jersey

December 11-18, 1787 (8 days)

38-0 (38)

Georgia

December 25, 1787 to January 2, 1788 (9 days) 26-0 (26)

Connecticut

January 3-9, 1788 (7 days)

128-40 (168)

Massachusetts

January 9 to February 7, 1788 (30 days)

187-168 (355)

Maryland

April 21-28, 1788 (8 days)

63-11 (74)

South Carolina

May 12-23, 1788 (12 days)

149-73 (222)

New Hampshire

June 18-21, 1788 (4 days)

57-47 (104)

Virginia

June 2-27, 1788 (26 days)

89-79 (168)

7

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R47619, The Equal Rights Amendment:

Background and Recent Legal Developments, July 11, 2023, p.8

8

Note. In Colorado, the state legislature passed Senate Joint Memorial 1 in 1978 to call an Article V Convention to develop a

Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA). In 2021, the Colorado state legislature rescinded all Article V Convention applications by

House Joint Resolution (HJR) 21-1006. Thus, the 1978 resolution was no longer valid. As of January 2025, HJR 21-1006 was

not posted by the Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives (

https://clerk.house.gov/SelectedMemorial

). In addition,

this website list various “Application” rescissions that are officially recognized by the U.S. Congress.

9

Note.

The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution,

Jonathan Elliot, 1876.

https://constitutioncenter.org/education/classroom-resource-library/classroom/4.5-info-brief-ratification-timeline/

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention

A-5

North York

June 17 to July 26, 1788 (38 days)

30-27 (57)

North Carolina

10

1

st

: July 21 to August 4, 1788 (15 days), the

delegates voted to “neither reject nor ratify”

2

nd

: November 16-21, 1789 (6 days)

1

st

: 184-84 (268,

indecision)

2

nd

: 195-77 (272)

Rhode Island

11

1

st

: March 1790 (adjourned without voting)

2

nd

: May 29, 1790 (1 day, continuation)

1

st

: No vote

2

nd

: 34-32 (66)

On March 1, 1788, the Rhode Island State Assembly passed the “Rhode Island Act

Calling a Referendum on the Constitution,” and it was an approval of the new ratification

methodology in Article VII of the U.S. Constitution.

12

“In effect, the Rhode Island legislature

made every voter a delegate to a dispersed ratification convention and handed them the authority

to determine whether the Constitution should be adopted or rejected. As predicted, the Rhode

Island voters overwhelmingly rejected the Constitution by a vote of 238 to 2,714. But the

rejection by the people of Rhode Island was procedurally no different from the rejection by

North Carolina’s delegates in its 1788 convention.”

13

In a way, this so called “dispersed

ratification convention” held by Rhode Island acted as its 1

st

state ratifying convention in 1788,

and then there were two more state conventions held in 1790 (March and May). Despite the

multiple conventions held by North Carolina and Rhode Island, the mode of ratification by state

level conventions proved very successful, and it represented the “true will of the people.”

In 1933, the mode of ratification by state level conventions was implemented for the 21

st

Amendment (i.e., repeal of prohibition under 18

th

Amendment) to the U.S. Constitution.

Congress wrote a time limit of seven years within the

amendment text

, and there was serious

doubt state level ratifying conventions would occur within the timeframe. There were 48 states

in the nation, and 43 passed statutes establishing a state level convention to consider the 21

st

Amendment. There were 39 state level conventions actually conducted, and 38 of them ratified

the 21

st

Amendment (36 of 48 states required). South Carolina was the only state to reject it, and

there were no rescissions made by any state.

14

The entire ratification process took 10 months to

complete, and all state level ratifying conventions occurred within the “space of a single day.”

15

The overall success of the state ratifying conventions was also characterized as capturing the

“true will of the people.”

As a mode of ratification, there is a greater probability the results of a state convention

will remain unchanged as compared the state legislature because it is extremely difficult to

10

https://northcarolinahistory.org/commentary/north-carolinas-ratification-debates-guaranteed-bill-of-rights/

11

National Archives:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2015/05/18/rogue-island-the-last-state-to-ratify-the-constitution/

12

Note. Rhode Island was the only state not to send delegates to the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, but it joined all states in

approving the new ratification methodology (i.e., 9 of 13 state ratifying conventions) explained in Article VII of the U.S.

Constitution. In the Articles of Confederation, Article XIII explains how any “alteration” must be “agreed to, in a Congress of

the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.” So, the new ratification methodology replaced

this statement in the Articles of Confederation after all 13 State Assemblies agreed to it.

https:%%//%%journals.law.harvard.edu/jlpp/wp-

content/uploads/sites/90/2017/03/Farris_FINAL.pdf/

Defying Conventional Wisdom: The Constitution Was Not the Product of a

Runaway Convention

, Michael Farris, March 2017, p114-116.

13

Defying Conventional Wisdom

, Michael Farris, March 2017, p117.

14

Ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States: State Convention Records and Laws

,

Compiled by Edward Somerville, 1939, page 5.

15

Ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment

, page 7.

Appendix A: Mode of Ratification – State Legislature vs. State Convention

A-6

conduct a second state convention especially if a state level statute is required to host it again.

For the state legislature, it is easier to seek a change to an original decision by just waiting until

the next state legislative session (assuming it is still within the time limit). In addition, there is

scholarly discussion that explains that a state convention can only be held once (i.e., “one and

done”). If this circumstance is true, it makes the results of a state convention absolutely final

with no opportunity for a later change. Thus,

there is

greater certainty the outcome of a state

convention will remain unchanged than a state legislature

, and it ensures the original ratification

(or rejection) of an amendment is more carefully considered before it becomes final.

Appendix B: Statistical Hypothesis Test in Support of State Convention

B-1

Situation. There are two approaches to proposing amendments as described in Article V of the U.S.

Constitution. The first approach involves Congress proposing amendments by 2/3’s super majority vote

in both chambers. The second approach involves 2/3’s of state legislatures (or 34 of 50) approving a

resolution for an Article V Convention to form to propose amendments. Afterwards, any proposed

amendments are then sent to the states where 3/4’s of the states (or 38 of 50) must ratify the amendment

for it to become part of the U.S. Constitution. The current 27 amendments originated from Congress,

and the second approach involving an Article V Convention has not occurred in U.S. History. The goal

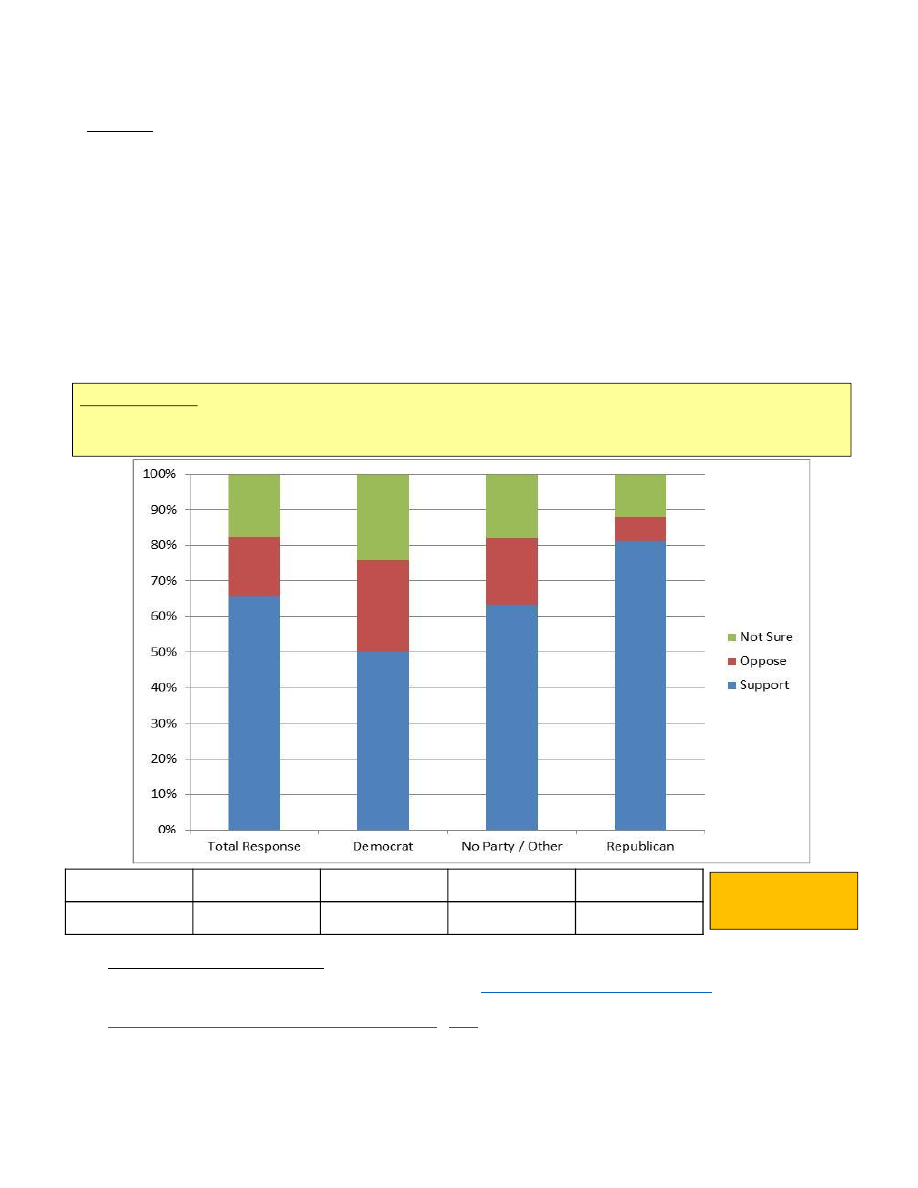

is to limit the power of the federal government. To understand the U.S. perspective, the Trafalgar Group

conducted a national survey, and the chart below provides an overall summary of it.

1

1

The actual survey results can be found at the following link:

https://conventionofstates.com/polling

. The Trafalgar

Group established a scientific methodology to conduct the survey, and it is described at the following link:

https://www.thetrafalgargroup.org/polling-methodolgy

.

Note. In August 2024, Susquehanna Polling and

Research (SB&R) had a similar question (and very similar results as “Total Response”), but it did not have

polling demographics like the Trafalgar Group. Thus, a similar statistical test is not feasible with the SB&R

survey results.

Survey Question: Would you support a Convention of States (COS) to meet and propose Constitutional

Amendments focusing on term limits for Congress and federal officials, federal spending restraints, and

limiting the federal government to its constitutionally mandated authority? (Support, Oppose, Not Sure)

35.6%

25.1%

39.3%

100%

% of Response

383

271

424

1078

# of Responses

65.7%

16.6%

17.7%

50.2%

63.3%

81.3%

25.6%

24.2%

18.8%

17.9%

6.7%

12.0%

Convention of States Action (COSA) National Survey Results: July 7-10, 2022

Conducted by

Trafalgar Group

Appendix B: Statistical Hypothesis Test in Support of State Convention

B-2

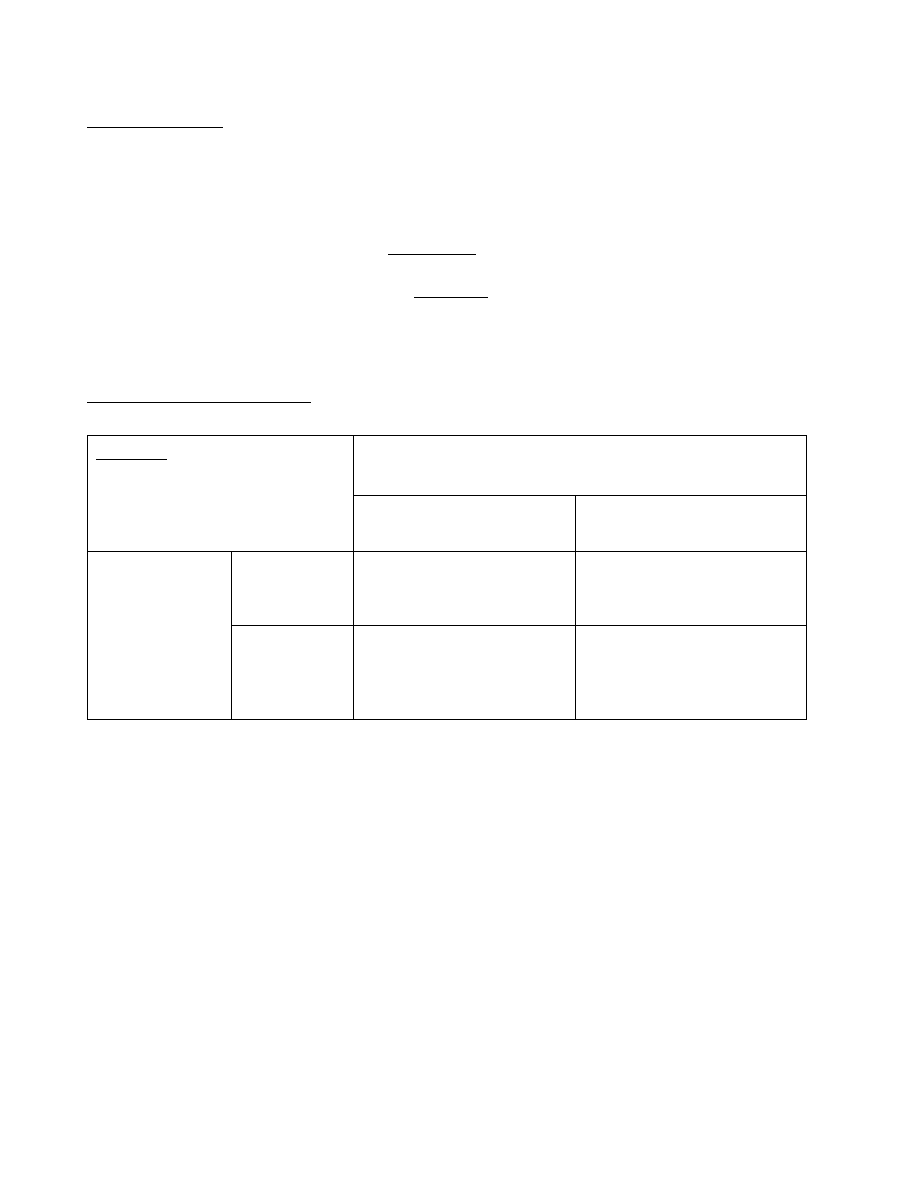

Research Question. For the survey results, there is an interest in understanding any potential

relationship between a person’s party affiliation and response. So, here is the following research

question to address this interest.

What type of relationship exists between a person’s party affiliation

and survey response (i.e., independent or dependent relationship)?

•

Null Hypothesis (H

o

): There is an

independent

relationship between a person’s party affiliation

and survey response.

•

Alternate Hypothesis (H

a

): There is a

dependent

relationship between a person’s party affiliation

and survey response.

•

Test Statistic. In this situation, there are two categorical variables under examination, and the

appropriate test statistic to use is a proportion (Chi-Squared Distribution Test).

Potential Error Types and Risk.

Overview. This table depicts the

multiple potential and possible

outcomes for this hypothesis test.

Decision Made

Accept H

o

Reject H

o

Situation

H

o

is True

Correct Decision.

Probability = 1- alpha (α)

Type I Error (false positive)

Probability = alpha (α)

H

o

is False

Type II Error (false negative)

Probability = beta (β)

Correct Decision.

Probability = 1- beta (β)

(a.k.a. Power)

For Type I Error alpha (α), the risk is that the hypothesis test concludes a dependent relationship exists

when the reality is that an independent relationship exists. The mitigation to prevent this error is to set a

level of significance (α) that is appropriately small. Typically, statisticians state alpha (α) = 0.05 is an

acceptable level. For purposes of this hypothesis test, alpha (α) = 0.01 level of significance.

For Type II Error beta (β), the risk is that the hypothesis test concludes an independent relationship

exists when the reality is that a dependent relationship exists. The mitigation to prevent this error is to

collect a fairly large random sample size that is representative of the U.S. population. Typically,

statisticians state a minimum random sample size is 30, and the survey has a random sample size of

1,078 individuals. Thus, there is a fairly large random sample size from the survey. In addition, this

sample size is large enough to yield a small standard error for the survey of +/- 4.2%. Thus, the

percentage of the American Population that supports the Article V Convention ranges 61.5% to 69.9%

(or 65.7 +/- 4.2%). This is clearly a vast majority.

Appendix B: Statistical Hypothesis Test in Support of State Convention

B-3

Hypothesis Test Re-stated Mathematically. Below is each hypothesis and corresponding mathematical

expression.

Null Hypothesis (H

o

): There is an

independent

relationship between a person’s party affiliation and

survey response.

•

Actual Survey Proportion = Expected Survey Proportion

Alternate Hypothesis (H

a

): There is a

dependent

relationship between a person’s party affiliation and

survey response.

•

Actual Survey Proportion ≠ Expected Survey Proportion

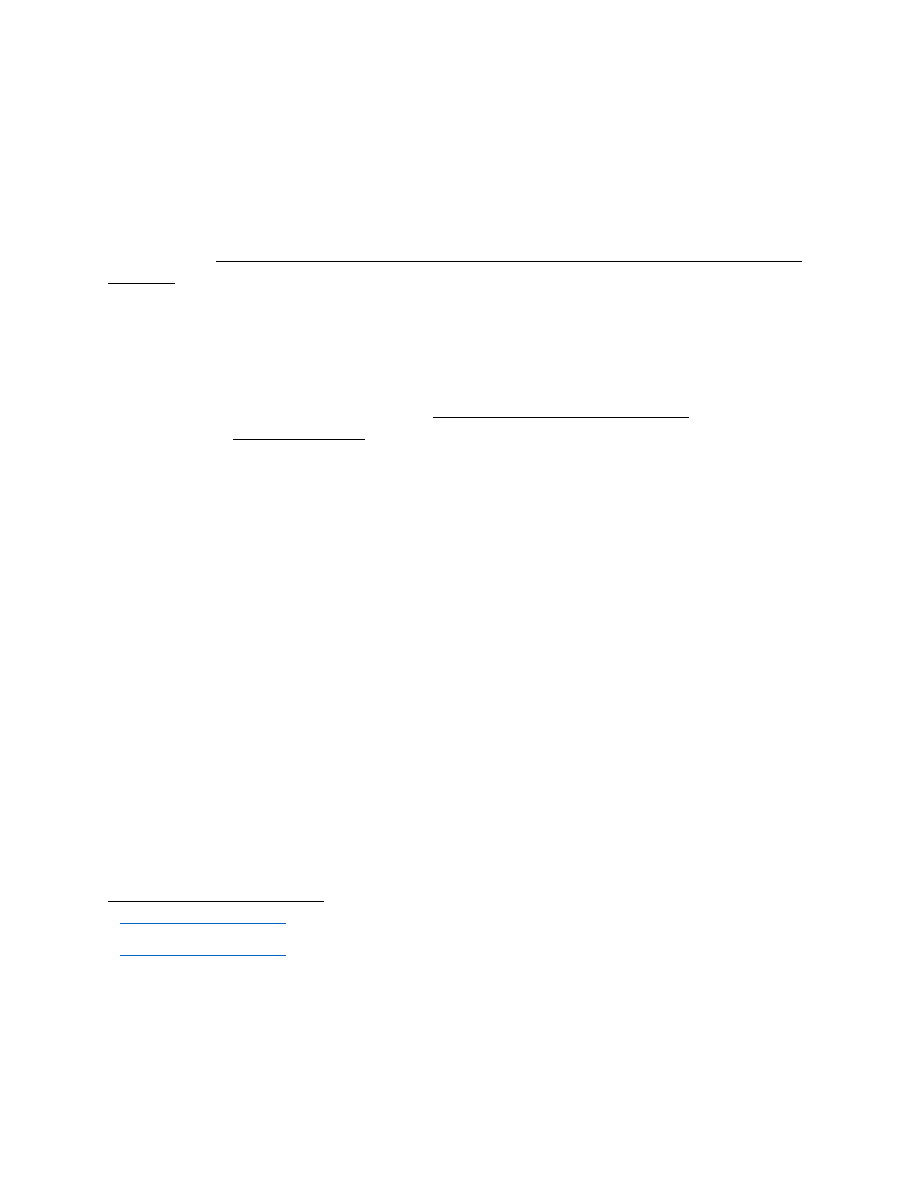

Data Analyzed. The following tables originated from a supporting excel spreadsheet.

2

In this case,

Table 1 is the actual survey data collected by the Trafalgar Group. Table 2 is the expected (or

calculated) survey data that is based on the fundamental mathematical definition of independence

[P(A∩B) = P(A)P(B)]. In the excel spreadsheet, there are two additional tables that apply this basic

mathematical equation as another reference point.

Table 1: Actual Survey Data

Table 2: Expected (or calculated) Survey Data

2

Note: The exact excel spreadsheet calculation is available upon request.

Democrat

No Party / Other

Republican

Total

Response

Not Sure

102

48

46

196

Oppose

109

51

26

186

Support

213

172

311

696

424

271

383

1078

Party Affiliation

Survey

Response

Survey Data

(Actual)

Total

Democrat

No Party / Other

Republican

Not Sure

77.1

49.3

69.6

196.0

Oppose

73.2

46.8

66.1

186.0

Support

273.8

175.0

247.3

696.0

424.0

271.0

383.0

1078.0

Survey Data

(Expected)

Party Affiliation

Total

Survey

Response

Total

Appendix B: Statistical Hypothesis Test in Support of State Convention

B-4

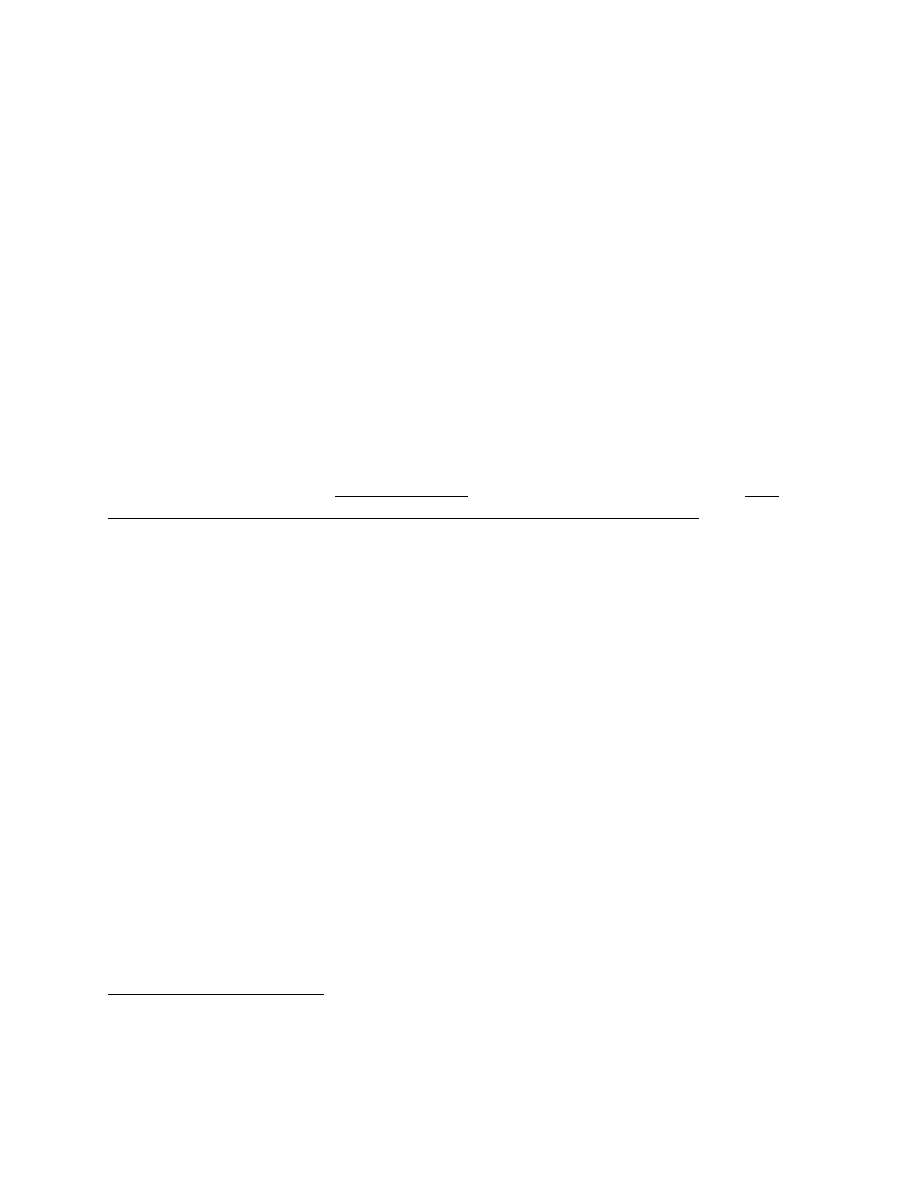

P-Value Calculations & Results. For this hypothesis test, the use of the Chi-Squared Distribution is

appropriate because it provides a p-value addressing independence between two categorical variables.

From the supporting excel spreadsheet, Table 3 depicts the p-value results and decision. Within excel,

the following formula was used to compare Tables 1&2:

=CHISQ.TEST(C10:C12,C18:C20)

.

Table 3: P-Value Results and Decision

In this situation, the overall (or total) decision is to reject the null hypothesis, and there is strong

statistical evidence to conclude a

dependent

relationship does exist between a person’s party affiliation

and survey response. Thus, the result answers the research question:

What type of relationship exists

between a person’s party affiliation and survey response (i.e., independent or dependent

relationship)?

Even though the overall (or total) hypothesis test concludes a dependent relationship does exist, there

was an interesting insight with the “No Party / Other” subcategory by itself. The calculated p-value

(0.79139) for this individual subcategory was significantly greater than alpha (α) = 0.01, and it means

there is an

independent

relationship with the survey responses. This specific result is an interesting

outcome because it indicates a potential attitude independent of political affiliation. In other words,

someone who is neither a “Democrat” nor a “Republican” is considered an “Independent.”

Overall Conclusion. The results of the statistical hypothesis test provide evidence that “Democrat” and

“Republican” responses are primarily based on “bias” (or dependent) because they are influenced by a

party affiliation / opinion. In the opposite way, the results of the overall statistical hypothesis test

provide evidence to support the “No Party / Other” responses are primarily “unbias” (or independent)

because they are not influenced by a party affiliation.

Support to State Convention. The results of this statistical hypothesis test support the need to have a

state convention vs. the state legislature as a mode of ratification. In the state legislature such as

Colorado, there are only Republicans and Democrats with some small number of other political parties.

Essentially, there are no “independents.” However, there is a greater opportunity to involve

“independents” in a state convention because it is a specific event held within a fairly short timeframe,

and it can be fairly equivalent as calling random citizens to participate in jury duty. Since a state

convention has a greater chance of involving “independents,” there is a greater chance for the event to

be “unbias” towards ratifying amendments (i.e., more objective than the state legislature).

Decision

Total

3.00319E-18

< 0.01

Reject Null

Democrat

3.24743E-09

< 0.01

Reject Null

No Party /

Other

0.791390572

> 0.01

Accept Null

Republican

2.58778E-11

< 0.01

Reject Null

Chi-Squared Distribution for Independence

P-Value (Chi-Squared Test)

P-Value (Chi-Squared Test)

P-Value (Chi-Squared Test)

P-Value (Chi-Squared Test)

alpha (

α

) = 0.01

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments

C-1

Since 1789, Congress proposed 33 Amendments to the states for ratification. There are

27 of these 33 Amendments that were ratified between 1791 to 1992, and the historical track

record is a fairly solid one (~82% success rate).

1

The table below shows their historical timelines

for ratification. The 21

st

Amendment is the only one ratified by state conventions, and the other

26 amendments were ratified by the state legislatures.

2

Amendment

Date Proposed by Congress

Date of Ratification

Timeframe

1

st

Bill of Rights proposed by

Congress on September 25, 1789.

Ratified December 15, 1791

Note: 27

th

Amendment was

part of the original bill

proposed in 1789. This

historical example shows how

all proposed amendments may

not ratify together. May also

happen with Article V

Convention proposed

amendments.

2.25 years

2

nd

3

rd

4

th

5

th

6

th

7

th

8

th

9

th

10

th

11

th

March 4, 1794

February 7, 1795

11 months

12

th

December 9, 1803

June 15, 1804

6 months

13

th

January 31, 1865

December 6, 1865

11 months

14

th

June 13, 1866

July 9, 1868

2.1 years

15

th

February 26, 1869

February 3, 1870

1 year

16

th

July 2, 1909

February 3, 1913

3.5 years

17

th

May 13, 1912

April 8, 1913

11 months

18

th

December 18, 1917

January 16, 1919

1.1 years

19

th

June 4, 1919

August 18, 1920

1.2 years

20

th

March 2, 1932

January 23, 1933

10 months

21

st

February 20, 1933

December 5, 1933

10 months

22

nd

March 21, 1947

February 27, 1951

4 years

23

rd

June 16, 1960

March 29, 1961

9 months

24

th

August 27, 1962

January 23, 1964

1.5 years

25

th

July 6, 1965

February 10, 1967

1.5 years

26

th

March 23, 1971

July 1, 1971

4 months

27

th

September 25, 1789

May 7, 1992

202 years

With the exception of the 27

th

Amendment, the historical record for ratifying amendments

is 4 years or less, and this represents another fairly solid historical track record. When it comes

to the other six unratified amendments, there is an interesting unique history for each one, and

they have a historical precedent that may impact future proposed amendments.

1

https:%%//%%crsreports.congress.gov

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R47959,

Proposals to Amend the U.S.

Constitution: Fact Sheet

, December 17, 2024, p.2

2

Source Archives Foundation:

https://archivesfoundation.org/amendments-u-s-constitution/

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments

C-2

The six unratified amendments proposed by Congress are listed below, and there is a

general status for each one of them.

3

Topic of Amendment Date Proposed to States General Status & Notes

Size of U.S. House or

Congressional

Apportionment

September 25, 1789

(note: part of original

“Bill of Rights”

proposal)

Still active? Very 1

st

Proposed

Amendment and no time limit for

ratification. 11 states ratified of 38 states

required.

4

Foreign Titles of

Nobility

May 1, 1810

Still active? No time limit for

ratification, and there is a question of its

current relevancy.

5

Protection of Slavery

March 2, 1861

No longer valid. Confederate States (11)

of America was formed. Later, 13

th

Amendment passed in December 1865.

6

Regulating Child

Labor

June 2, 1924

Still Outstanding/Stalled. No time limit

for ratification. 28 states ratified of 38

required. Most recent state to ratify was

1937; stalled for lack of momentum.

7

Equal Rights

Amendment

March 22, 1972

No longer active. Congress set original

time limit to pass within 7 years. 35

states ratified of 38 states required.

Congress provided extended timeline of

3 years but no additional states were able

to ratify. Some groups disputed the

inactive status for years.

8

DC Voting Rights

August 22, 1978

No longer active. Congress set original

time limit to pass within 7 years. 16

states ratified of 38 states required. No

dispute from any groups.

9

Beginning with the 18

th

Amendment (Prohibition), the U.S. Congress started to impose a

timeframe of 7 years for ratification even though Article V of the U.S. Constitution did not

specifically provide this power to the U.S. Congress.

10

The origin of the 7 years timeframe came

from U.S. Senator William Harding who used it as a political tool to “permit him and others to

vote for the amendment, thus avoiding the wrath of the ‘Drys’ (e.g., Anti-Saloon League).” At

3

https:%%//%%crsreports.congress.gov

/ Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R47959,

Proposals to Amend the U.S.

Constitution: Fact Sheet

, December 17, 2024, p.2

4

Source National Archives:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/01/23/unratified-amendments/

5

Source National Archives:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/01/30/unratified-amendments-titles-of-nobility/

6

Source National Archives:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/02/19/unratified-amendments-protection-of-slavery/

7

Source National Archives:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/03/24/unratified-amendments-regulating-child-labor/

8

Source History of ERA:

https://www.equalrightsamendment.org/pathstoratification/

9

Source National Archives:

https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/06/17/unratified-amendments-dc-voting-rights/

10

https:%%//%%crsreports.congress.gov

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42589,

The Article V Convention to Propose

Constitutional Amendments: Contemporary Issues for Congress,

March 29, 2016, p.26

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments

C-3

the same time, he expected time would run out before it was ratified.

11

The 18

th

Amendment was

ratified in 1.1 years, and it was clearly within 7 years. Eventually, there was debate as to whether

Congress could impose a time limit because Article V of the U.S. Constitution did not specify

this power to Congress. However, U.S. Supreme Court Cases

Dillion v. Gloss

(256 U.S. 368,

year 1921) and

Coleman v. Miller

(307 U.S. 433, year 1939) both upheld that Congress had the

power to “fix a definite period for the ratification” of amendments.

12

Overall, there are 10

historical amendments with timeframes associated with them for ratification, and there is a

distinction to note that some of them had the timeframe written within the

amendment text

and

others within the

joint resolution statement

made by Congress.

1.

18

th

Amendment (amendment text)

2.

20

th

Amendment (amendment text)

3.

21

st

Amendment (amendment text)

4.

22

nd

Amendment (amendment text)

5.

23

rd

Amendment (joint resolution statement)

6.

24

th

Amendment (joint resolution statement)

7.

25

th

Amendment (joint resolution statement)

8.

26

th

Amendment (joint resolution statement)

9.

Equal Rights Amendment (joint resolution statement)

10.

DC Voting Rights Amendment (amendment text)

The actual timeframe written within the

amendment text

of the five amendments became

officially part of the amendment itself and could not be changed. Thus, the timeframe for

ratification for these amendments could not be changed. However, the timeframe for ratification

written within the

joint resolution statement

by Congress could be changed because it was not a

permanent part of the amendment itself. The 18

th

, 20

th

-26

th

Amendments did not encounter any

issues with the timeframe requirement with either the

amendment text

or

joint resolution

statement

approaches. When the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) was introduced in 1972, it

had a 7 year timeframe for ratification, and 35 states ratified it within the timeframe. However,

38 states were required. Consequently, Congress extended the deadline for another 3 years, yet

no additional states ratified the amendment. So, it was widely considered expired, but supporters

of the ERA argued otherwise. It was disputed for years.

13

In 1978, Congress proposed the DC

Voting Rights Amendment, and it wrote the timeframe for ratification within the

amendment text

to become a part of the amendment itself and to avoid any controversy like the ERA. Eventually,

the DC Voting Rights Amendment only acquired 16 states to ratify it when 38 states were

required. The timeframe of 7 years expired, and the amendment failed with no dispute.

14

11

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42979,

The Proposed Equal Rights

Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues

, December 23 2019, p.28.

12

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42979,

The Proposed Equal Rights

Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues

, December 23 2019, p.26-27 (section on “Role of the Supreme Court Decisions in

Dillion v. Gloss

and

Coleman v. Miller

”).

13

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42979, The Proposed Equal Rights

Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues, December 23 2019, see “Summary” page.

14

https://crsreports.congress.gov/

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R42979, The Proposed Equal Rights

Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues, December 23 2019, p. 30-31

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments

C-4

The historical background of these ratified and proposed amendments to the U.S.

Constitution informs important lessons for consideration during the actual implementation of an

Article V Convention. Based on original intent, the framers of the U.S. Constitution granted the

same powers for an Article V Convention to propose amendments as the U.S. Congress. More

specifically, “the Article V Convention device was intended to provide an alternative method of

amendment, but it was also intended that a convention should enjoy a broad national consensus

of support and

meet similarly exacting standards as those that apply to amendments proposed in

Congress

.”

15

From this critical concluding statement from the Congressional Research Service

(CRS), it appears an Article V Convention has the same exact powers as Congress for proposing

written amendments to the U.S. Constitution to include a timeframe for ratification (e.g., 7 years)

and mode of ratification (state legislatures or state conventions). For example, each proposed

amendment from an Article V Convention could have the exact same written language as the 21

st

Amendment that reads: “Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been

ratified as an amendment to the Constitution

by conventions in the several States

, as provided in

the Constitution,

within seven years

from the date of submission hereof to the States by the

Congress.” However, there are multiple scholarly references throughout the various CRS reports

on an Article V Convention that explain it does not have the same exact powers as Congress for

written proposed amendments.

16

So, what is some of this scholarly discussion?

With respect to the timeframe for ratification, the Article V Convention shares the same

power as Congress for specifying a time limit because it is the proposing “agency” that also

specifies the timeframe. If the Article V Convention proposed an amendment without specifying

a timeframe for ratification, Congress could circumvent any proposed amendment it does not

support by specifying a timeframe for ratification such as 6-weeks. In this scenario, it is highly

unlikely 38 of 50 states will have enough time to ratify the amendment. To ensure this does not

happen, the Article V Convention should write the specific timeframe for ratification (e.g., 7

years) within the

amendment text

to become part of the amendment itself, and Congress cannot

change any language in the written proposed amendment.

17

With respect to the mode of ratification, an Article V Convention does not share the same

power as Congress. Congress has the power to specify the mode of ratification only for those

proposals within the Article V Convention call scale and scope. For example, the basic Article V

Convention commission is to “limit the power of the federal government,” and it cannot make

any proposed changes to the “Bill of Rights.” If the Article V Convention proposed an

amendment for term limits for members of Congress and another repealing the 1st Amendment,

15

https:%%//%%crsreports.congress.gov

Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report R44435,

The Article V Convention to Propose

Constitutional Amendments: Current Development

, November 15, 2017, p.20

16

https:%%//%%crsreports.congress.gov

- three CRS reports on Article V Convention.

1) CRS Report R42592,

The Article V Convention for Proposing Constitutional Amendments: Historical Perspectives for

Congress

, October 22, 2012

2) CRS Report R42589,

The Article V Convention to Propose Constitutional Amendments: Contemporary Issues for Congress

,

March 29, 2016

3) CRS Report R44435,

The Article V Convention to Propose Constitutional Amendments: Current Developments

, November 15,

2017

17

Proposing Constitutional Amendments by Convention: Rules Governing the Process

, by Robert G. Natelson, 78 Tennessee Law

Review 693, year 2011, p.750.

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments

C-5

then Congress would only specify a mode of ratification for the term limits amendment. The

other one would not be sent to the states for consideration. In this regard, Congress’ power is the

“same as if it had proposed the amendment” itself.

18

In a way, Congress serves as another check

to ensure the Article V Convention does not exceed its commission authority for proposed

amendments. Even though the Article V Convention proposed amendments do not have to

technically pass through Congress, the Constitution does mandate that Congress select a mode of

ratification for each one. It is possible for members of Congress to view selecting a mode of

ratification as a “discretionary duty,” and they would decide to do nothing with the proposed

amendment(s). Thus, they would sit dormant and not be sent to the states. If this sort of event

occurs, the Constitutional mandate for Congress to select a mode of ratification “should be

enforceable judicially.”

19

During the Article V Convention, there is a potential forcing function that commissioners

could write within the

amendment text

of each amendment itself to ensure Congress does not try

to circumvent the proposed amendment. As an example, each amendment can have

amendment

text

incorporating both timeframe for ratification and mode of ratification in the following

language: “Section #. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an

amendment to the Constitution

within seven years

from the date of its submission to the

state

legislatures or conventions in accordance with the fifth article of this Constitution

. This article

shall become effective six months after ratification as an amendment to the Constitution.”

20

Here

are some benefits from including this example language within the

amendment text

.

•

The amendment contains seven years as the timeframe for ratification, and

Congress cannot change it or modify it later. The historical lessons learned from

the Equal Rights Amendment and DC Voting Rights Amendment ensure it.

•

The timeframe of ratification does not start until it is submitted to “state

legislatures or conventions.” It does not say time starts when submitted to

Congress for review. If Congress decides to delay its selection on a mode of

ratification for six months or a year for instance, the delay of six months or a year

are not counted against the seven years. If Congress delays longer than a year

with no sign in sight on when selecting a mode of ratification, then any time used

to enforce judicial action against Congress is also not counted against the seven

years.

•

The amendment includes both modes of ratification, but it does not specify which

one to use. In this manner, the Article V Convention is not trying to circumvent

the power of Congress to select a mode of ratification.

18

Proposing Constitutional Amendments by Convention: Rules Governing the Process

, p.748.

19

Proposing Constitutional Amendments by Convention: Rules Governing the Process

, p.749.

20

A Proposed Balanced Budget Amendment

, by Robert Natelson, July 27, 2017, The Heartland Institute. Note: in this published

article, the author explains a potential Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA) proposed by an Article V Convention. The author

incorporates a section addressing the timeframe for ratification and mode of ratification.

Appendix C: Historical Ratification of Amendments

C-6

Upon completion of the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, the President of the Convention

George Washington sent his executive letter to the Continental Congress with the

recommendation for a mode of ratification involving conventions of the several states. State

conventions as a mode of ratification were also stated within the language of Article VII of the

U.S. Constitution.

21

The executive letter idea is a historical precedent the Article V Convention

could follow to recommend the state convention mode of ratification, but there is no guarantee

the U.S. Congress would accept the recommendation.

This historical examination into the ratification of U.S. Constitution Amendments is

critical background for consideration in an Article V Convention and Colorado Ratifying

Convention (and other state conventions for that matter).

21

Resolution Transmitting the Constitution to Congress in Convention

, Monday, September 17, 1787, signed by President George

Washington. Note: the executive letter served as a summary of the overall convention results and way-forward for ratification of

the base U.S. Constitution.|

|

—-

| Page Metadata ||

|Login Required to view? |No |

|Created: |2025-03-14 23:48 GMT|

|Updated: |2025-03-14 23:48 GMT|

|Published: |2025-03-14 23:48 GMT|

|Converted: |2025-11-11 12:35 GMT|

|Change Author: |Vivian Garcia |

|Credit Author: |Mike Forbis |